Q: I recently heard a teaching about Genesis 1:26 that I’m confused about. The verse says, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” I was always under the impression that this pointed to the Trinity, although it’s not explicitly stated. However, this pastor was saying it’s NOT the Trinity but rather that it’s referring to “God and his divine council made up of sons of God, created in the image of God and share in the reign of the spiritual world with God” (direct quote from his sermon). I had never heard this before and feel like this is a poor exegesis of the text. I did a little research, and I think he pulled it from Michael Heiser’s work (possibly his book The Unseen Realm). I feel like it’s a little controversial. This pastor’s teaching is bothering me, but I don’t have much knowledge to really back up why I feel that way!

When you come across something that sounds skeptical, what you should do to look and look and look at the text, and then look at the text some more, to see if what is being said actually does match up with it. It’s the looking at the text part that many people don’t do, when it comes right down to it. And it is the same with this particular textual problem.

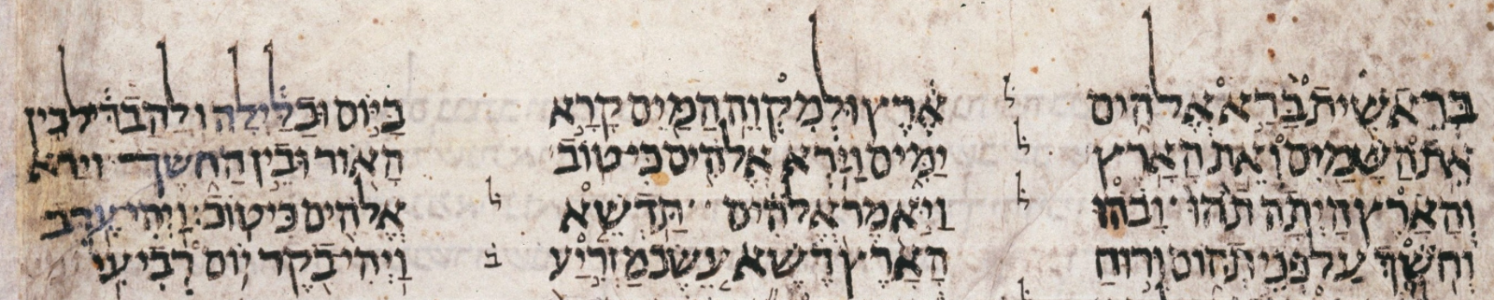

It is very common among Christians to understand the plural pronouns used in God’s speech in Genesis 1 as evidence for the Trinity. And indeed, as a Christian that is how I understand them. At the same time, however, I absolutely must affirm that I read the text this way because I am importing Trinitarian theology (post-Incarnation of Jesus) back into that pre-Incarnation text. There is nothing in Genesis 1 itself that would lead us to read that speech of God as some sort of Trinitarian conversation.

However, the “Divine Council” view of that speech is also not substantiated anywhere in the Genesis 1 text. That view, whether it comes from Michael Heiser or others, is a projection onto the text of other information about the ancient Israelite conceptualization of the heavenly realm (either from other parts of the Bible or from other extra-biblical sources). This means that the Divine Council view is just as problematic as the Trinitarian view in terms of the exegesis of the actual text itself.

When we read Genesis 1 and come across the plural pronouns used by God in his speech, we should look at the local text for clues regarding how to understand that peculiar aspect of the text. In the case of Genesis 1, there are two clues which can help us. First of all, the word for God is plural instead of singular. Now just because a word is plural does not mean that the referent is plural. A plural form in Hebrew can refer to something singular, similar to how “pants” in English refers a singular article of clothing even though the word itself uses a plural form. So it is possible to read the Hebrew plural form for God as somehow referring to some kind of multiplicity in God, but it is not assured simply from the form itself. Secondly, there is a reference to a “spirit of God” in Genesis 1:2. Of course, this brings up the question: “How does the ’spirit of God’ relate to ‘God’ within the conceptual world of the author writing the story?” And we don’t know the answer to that question. I’m only saying that, if we read the text itself and look for the contextual clues in the local context, the plural pronouns in reference to God would appear to refer to some kind of relationship between “spirit of God” and “God.”

Of course, Christian Trinitarian theology quickly speaks up and suggests an answer. And rightly so, if we believe the manifold witness of Christian interpreters throughout the centuries. However, as I said earlier, we must affirm that that view does not truly arise from the text itself but is rather a later explanation of the text provided after Jesus came to earth as revealed to us that God is Trinity and not simply unity.

If we want to speak strictly about the point of view of the Genesis author, we must confess that we don’t know what the author had in mind when God speaks using plural pronouns. It is a mystery of the text. In theory, the “Divine Council” might be correct…but it could just as easily be incorrect. It’s really just speculation. And most of the time, as an exegete and theologian I usually prefer to stop at the place of mystery rather than speculate on solutions that could just as easily be wrong as right. Generally speaking, I think it’s a wiser way to handle the Scriptures.

Seriously? Psalm 82:1-2

1 God has taken his place in the divine council;

in the midst of the gods he holds judgment:2 “How long will you judge unjustly

and show partiality to the wicked?

He can’t be speaking to Jesus and the Holy Spirit. They do not judge unjustly. He is clearly speaking to a council of angels. Look at the hebrew, it’s Elohims plural.

Psalm 82:6-8

6 ¶ I said, “You are gods,

sons of the Most High, all of you;7 nevertheless, like men you shall die,

and fall like any prince.”fn8 ¶ Arise, O God, judge the earth;

for you shall inherit all the nations!

God is clearly telling the lowercase elohim who rebelled against him that they will die like men. Like men. So, clearly, they are not men. They are lowercase elohim. Not God, not gods, nor gods in their own right, but that they are of spirit, not flesh. So, verse 8. Who is God calling God here? Saying you shall inherit all nations? It’s Jesus. Remember, this is before Jesus incarnate upon the earth. This proves the Trinity and the divine council. This is proof as to why demons recognize Jesus as Son of man.

LikeLike

I think this is a lovely balanced view

LikeLike

I think the best evidence for the divine council reading is the fact that these texts were written several hundred years before the first conceptualizations of the Trinity.

The very earliest we currently have of the idea of the Trinity is from Theophilus of Antioch (late 2nd century CE) and Tertullian (late 2nd to early 3rd century CE), around 180 CE. For the sake of argument, let’s just randomly say trinitarianism was a thing in 50 CE, fifty years earlier. Genesis is generally agreed to have been composed around the 6th century BCE during the Babylonian Exile. Furthermore, it draws from much older Mediterranean and Mesopotamian creation myths from as far back as the 9th and 10th centuries BCE. Thus, the writers of Genesis would have not been aware of the Trinity–It was not an idea at the time.

Other nods to the divine council are found in Deuteronomy 4, 7, 28, 32, Psalm 24, 29, 51, 82, Exodus 15, Isaiah 47, 40, Zephaniah 2, 1 Kings 18, Ecclesiastes 7, Judges 7, and Jeremiah 10, among others.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1276&context=lts_fac_pubs#:~:text=This%20article%20argues%20that%20the,mean%20what%20it%20plainly%20says. – Michael Heiner’s Monotheism, Polytheism, Monolatry, or Henotheism? Toward an Assessment of Divine Plurality in the Hebrew Bible

LikeLike