Recently I sat down with a pastor acquaintance of mine to chat about an upcoming sermon on sexual identity. This pastor wanted to pick my brain as they prepared to preach, and we recorded our conversation. The pastor’s voice is in bold type, and my voice is in italics type. Enjoy!

In our church we’ve been doing a series through the book of Proverbs over about seven weeks, using proverbs as wise sayings. Like it’s the end of the year with your family around the house and just talking about some wisdom and giving wisdom into certain issues. We’ve touched on finances and sex and pornography, so it’s been those kinds of issues. What I’m doing this week is talking about sexuality. I’m doing sexual identity from the perspective that sexuality was created by God. That we have a sexual identity which is not defined by what we have or what we desire or anything like that. Rather, who we are in God is who we are, outside of those things. So what do our desires mean to our humanity? The things we have, for instance, the gift mix that we have, the things that we’re born with, what do those things mean about our humanity? And so, what are the things that are true about identity, regardless of how we feel, what we desire, or what we have. Then, I would like to speak to the community about how then do we exist as a community with the reality that people are born with, you know, our biology. How do we exist with the tension that is in Scripture? Then, informing us to view the world this way and to view ourselves this way, but we’ve got these experiences that people have that seem to contradict what the Scriptures say. How do we help people integrate into the community and accept them as being an extension of the image of God, even though they feel a particular way––they might be inclined to recognize themselves or identify in a particular way? So in all of that, I think that the anchoring theme for me is identity.

And then I would like to give some good scriptural analysis for people. Because I think a lot of people inherit beliefs or philosophies, but we don’t really understand how we actually look at the Scriptures around this issue. So I would appreciate input around the Old Testament. There are people who just go, “It’s in the Old Testament.” I’ve got friends within this community always complaining that their biggest barrier is that they feel like Christians pick and choose what they’re going to be passionate about. That we’re going to stand on this issue, but there are so many other things, too! There’s so many laws in the Old Testament that even if you try, you can’t appropriate them in the New Testament just by virtue of the fact that cultures change and so forth. But when they’re speaking to Christians, they feel like Christians have this staunch approach to this one issue, but they don’t actually know why the other laws are not applicable, or even the ones that can be applicable feels like, “But why aren’t you doing this one?” because you could be.

And finally, how do we catch God’s heart? Because another thing that I’ve experienced on the other side of these sermons is there’s the clarity of Scripture but God’s heart is not always translated. It’s like “Here’s the line,” but what does that mean for people who feel on the other side of that line? I mean, I don’t think you can stay away from this topic being a campus missionary for as long as we have been. But I think this is fairly new looking at it from an identity perspective and creating a framework to help people gain clarity around how they go about thinking about it. For me as a preacher, I’m coming in on a Sunday, people are seeing these issues differently, and I want theological clarity for people. Then I also want people who are in that community not to see themselves as people who need to do something to be seen as whole, to be seen as an extension of the image of God, so I think if I would summarize my goals that’s what I’m trying to do.

Wow, that sounds really good. I’m so glad! So, if I can summarize what I hear you saying, you would like to focus your sermon especially on the idea of sexual identity or gender identity, and what is some sensical biblical thinking about that. And then, how to communicate that not just in an academic headspace, but in a way that God’s passion and love really come through. That’s what I hear you saying you want to do. That’s fantastic.

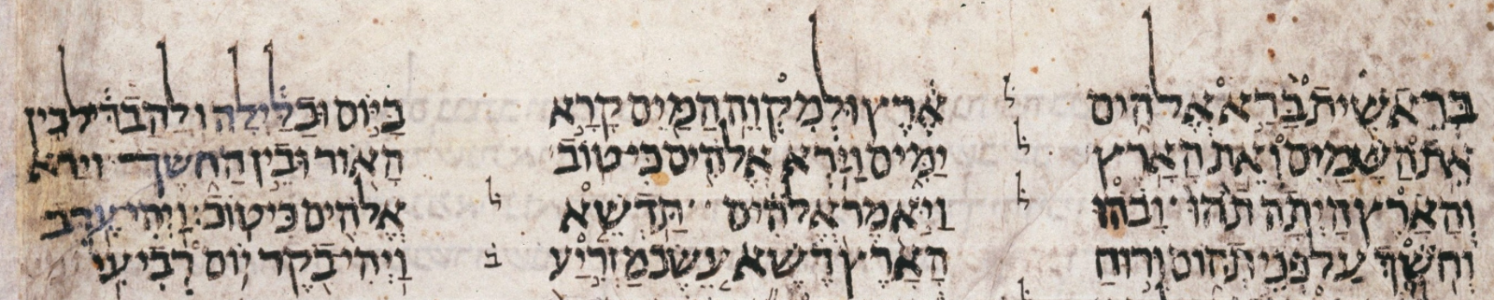

So I definitely think that Genesis 1 is really important. I don’t know what kind of theological background you’re coming from, or your specific church. But I feel like, when it comes to biblical thinking about gender, that portion of Scripture is really important. I’ll say that I myself grew up in a fundamentalist and patriarchal kind of upbringing. And largely through my own study of the Scripture I have come to think that those perspectives are just wrong. I think the picture of gender identity with God is that neither men nor women have a trump card in terms of the nature of God. Both genders together exhibit the image of God. Now I’m getting into more theology now as opposed to just exegesis, but I would say that the reason why we use male pronouns for God is because that’s what Jesus used. It’s not because God is somehow intrinsically male or female. Or, if you want to say it this way, it’s like God is both male and female at the same time.

Can I just ask you a question on that? I’ve heard some theology lectures where God is no longer referred to as he or she, but they say “God-self.” So how do you bring clarity around that? I hear what you’re saying that Jesus refers to God as “he” but that God is neither he nor she. What is the correct framework for that?

Yes, so again, this is a distinction that’s important for me as a theologian, and as a biblical exegete. Theology and exegesis are not strictly the same thing. Those are distinct disciplines, and theology goes further than exegesis does. At some point, your exegesis has to be founded on some presuppositions, and those presuppositions are your theology. It’s important for me to make that distinction, that this stuff we’re talking about right now has to do with one’s faith commitments about God. Right, so you can’t exegete your way to your faith commitments about God necessarily. At some point, all of us as Christians have to take what Scripture says, and then we choose what we believe about God. And this idea of gender identity is clearly in that realm of theology. Christians do come to different conclusions about these things, and it’s not necessarily a matter of right or wrong. Although, there is such a thing as good theology and bad theology.

So, now that I’ve kind of clarified that disclaimer, I’ll keep talking. So let me come back to another kind of faith commitment I have that I think is very important for theology. I am a firm believer that the non-physical aspect of our being, or non-physical aspect of reality, is reflected in physical aspects of reality. And I think that’s so important in all kinds of ways. We as people, how God has created us, we are not disembodied. We are not disembodied spirits that just happen to live inside a body. At some point when we die, we will be a disembodied spirit outside a body. But right now, we’re a whole being. We have our spirit and our body, and you can’t really pull those apart. There are all kinds of different ways that Christians have gone about trying to explain the differences between masculinity and femininity, and in the end I think most of those constructs are unsatisfying in terms of how the genders actually relate to one another.

In a marriage relationship, at least, I think the male partner is the penetrating partner and the female partner is the penetrated partner. And I think it’s the same in our relationship with God. This is my own thinking now. I think that the reason why God uses masculine pronouns for himself in his revelation to us is to show that in our relationship with God, he is the one who penetrates us, we are not the ones who penetrate him. So that’s how I reconcile that in my own theology. That’s my own personal thinking. But I think we have to read the revelation of God in Scripture in light of this fundamental truth that is set forth at the very beginning, that the image of God is both genders together. Neither one has a privileged position over the other. Now I understand that we could get into some stuff in the New Testament about preaching and stuff like that, but we don’t need to do that right now.

The other thing that I would say is that this differentiation between “penetrating” and “penetrated” really only applies within a sexual relationship. Apart from that, men and women really do stand on their own in God’s economy. I don’t think the idea is scriptural that a woman is under her father’s authority until she gets married and then her authority transfers to her husband. I think that is just bogus. All of us as Christians, we’re all under Jesus. Jesus says, “All authority is mine.” We’re all under Jesus. So those are my thoughts on Genesis and why I think Genesis 1 is so important. But you said that your series is really in Proverbs?

Yeah, so the wisdom is drawn from Proverbs, but it’s obviously very difficult just to preach out of Proverbs. Generally, I think the whole proverbs thing means just the wisdom literature around it. And that’s what has allowed for conversation, the tone of the preaching has allowed it because we’re talking wisdom literature. We’ve been able to take the posture that Proverbs has, sort of thinking around the Scripture to help how people think through things. Because that’s what proverbs do: as you look at it, it’s not obvious, and so it goes. So it’s been a nice way to see and hear preaching differently.

Do you have a specific passage that you’re focused on in Proverbs?

Not at the moment. Generally, what I do is to zoom out before I zoom in. I’m currently in the zoomed out phase. The reason why I thought it would be good to speak to you is because we just came out of the Proverbs series. So…okay, what’s the appropriate way to use the book of Proverbs to tie in, or at least link, the concepts from Genesis 1 and Romans 1 to put it all together.

Right. So let me ask you, what are you hoping to appropriate from Romans 1 specifically?

So the reason why I like Romans 1 is because it speaks about choosing to dishonor God. And there are ways in which God removes himself when there’s that dishonor, where we’ve chosen something other than God. What I’d like to do with Romans 1 is speak about how the ordering of our affections is important, right? And when our affections are not ordered, our submission is not ordered, it has consequences. It’s like society likes to order affections to our own lives, but there’s a reason for God’s order. And that if we don’t subscribe to that order, this is what happens. So I like Romans 1 for that.

Right. Okay, so I’m just going to share thoughts that come to mind. What is troubling, at least in a modern context with the current kinds of social debates about gender identity and sexual expression and stuff––one of the reasons why this is hard for Christians is because if you read the Bible, it is impossible to escape, and particularly in the New Testament. that our relationship with God affects what we do with our genitals. The Bible is very clear about that. Which makes perfect sense, right? If it’s true that we are made in the image of God, and God has made us male and female. And if our world has been marred by sin, it makes sense that sometimes those boundaries don’t work exactly the way that one might feel like they should. I mean, things like gender dysphoria make sense in a biblical worldview. God has created us male and female, and yet here we exist in a world that has been marred by sin. It makes sense that those things would not always work perfectly. But actually, thinking about the problem isn’t necessarily the issue, right? It’s how do we solve these problems? That’s what’s hard. But in the end, you cannot escape this fact that how we relate to God does, in fact, impact what we do with the male or female parts of our body. Paul is very clear about this.

For my own self, I think the path of wisdom is to say that it is not my place to change others. I have people very close to me who are Christians and are homosexual. How I have dealt with that, personally, is to say that it is not my place to change them. It’s my place to love them. I don’t condone homosexual behavior, I don’t think it’s in God’s will. But at the same time, I think that there are more important things in our Christian expression. I mean, I’m not just going to say to someone else, “I’m not going to talk to you” or “I’m not going to be your friend” just because you’ve come to a belief that homosexual expression is okay in your relationship with God. If I got into an honest conversation, what I would say is that I don’t think homosexual expression matches what the Bible reveals. But at the same time, I would say that sexual ethics is an issue of theology. It’s not really an issue of exegesis. So it’s an issue of faith. Yes, and another reason why it’s hard is because we have this big verse in Galatians where Paul says that, in Christ, there is no longer Jew or Gentile, or even male and female! So we’re like, “Oh, what is Paul really saying about gender identity there?” I don’t think he means it in a physical way. I don’t think he means that just because I’m a Christian, that doesn’t make me not a man anymore. I think what he means is something like, it’s often tempting for me as a man to just view myself as being a man and then, when I interact with women, to say, “Well, you don’t understand because you’re a woman.” Basically, I think Paul’s point is that that kind of thinking for Christians is not allowed. We’re not simply men and women anymore, we are all under Christ. Even further, there is something going on in our person when we come to Jesus and the Holy Spirit begins his work in us. My very manhood is, in fact, being changed. I’m becoming a new man.

I’m reminded of Jesus’ story to the Sadducees. They ask him a question about the woman who marries seven different brothers and then eventually dies, whose wife will she be in heaven? They’re trying to trap him because they believe there really is no such thing as a resurrection. And he says no, you’ve got it all wrong. In the eternal state, when we are with God, we won’t be married. This kind of inter-dynamism of the two genders in the gift of marriage is God’s gift for us while we are living. But in the eternal state, there’s something else for us, like we really will be individual people in our relationship with God.

While all these things are true, I think the weakness of this is coming to some kind of strictly individualistic view of my relationship with God, which Paul is also very clear that that is not what’s happening. The new self, the new man that God is making in me, as a Christian is not an individual identity, but is a communal identity. It’s all of us, as the body of Christ together. I think all of these things are woven into this idea of gender identity.

Bringing my thoughts back to Romans now, I think you are right. It’s a principle of the world that what we sow is what we will reap. What we do with our genitals is going to impact us either for better for worse, and I don’t know if anyone other than God is really in a position to know specifically what we deserve and what we don’t. But I think it is biblical wisdom to say. As a man, if I were to choose to sleep around, I would lose my marriage. I think we are on safe ground to preach that from a pulpit. I think the Bible is very clear that God has given us free will to make our own moral choices, but that we will reap the consequences of those choices for good or for ill.

Yes, so I have two questions on opposite ends. First, what is good news for the homosexual? How do we preach good news to somebody who is in that position? And then the second one is, as a community of faith, how do you walk with somebody faithfully, speaking directly to the person who finds themselves wrestling? So, what is the good news for person individually, and then the other end as a community of faith, as the body? How do we love faithfully? I find it easier in my personal relationships than in relating to people as a pastor. Because in your personal relationships, you know what you think. But when you have that pastoral role, or when people are in church and you’re thinking of yourself as a disciple maker, I think that community makes it a bit complicated. I don’t find it to be complicated at all in my personal relationships. But I do find it to be complicated in the body.

That makes perfect sense, because in some ways that community is looking to you for answers and for guidance.

Yeah.

I’ll just let you know that I’m not a pastor now, and I’ve never served a church as a pastor. So I’m only speaking from my experience as a Christian friend, a Bible teacher, a small group leader, a person who has preached occasionally but not specific pastoral experience. I need to be forthcoming about that. Let me ask you, is this a major issue in your church community?

It isn’t a place for conversation around it. But what people can’t deny is that the pervasive culture is growing, like the pride experience, that whole thing is growing. And people don’t know how to engage, so they are just sort of hiding. So I think I would be mostly speaking to our community of faith and rebuking them for their own identity idolatry. So that’s another thing that’s strong in my heart, that we have our own identity altars that we worship. And yet we say that this [homosexual] community has been wrong for doing the very thing that we do. So that’s something that I will mention. I think the the whole concept of identity is a strong one. And to highlight that this is an identity issue and we all wrestle with that in different ways. So I’m hoping that if people would see the ways in which they have their own identity idolatry, they’ll be able to walk more faithfully with others and see all of us as people who need Christ. And it’s manifesting in different ways, but in a way, I can relate because I’m struggling to lay down my own altar, so I’m not expecting others to do something that I’m not doing myself, so I’m hoping to bring it from that perspective.

Okay, so these are a few thoughts I have. It’s similar to the way that children are a gift from God. Nothing more, nothing less, right? None of us are promised children, which seems so counterintuitive. It seems like having babies is just what we do. But actually, the Bible says that children are a gift from God, which means that if God chooses not to give us children, we are not really in a position to be angry with God about that. Even though that, what I’ve just said, that’s really hard. For someone who is not able to have a baby, that’s a really hard thing. I’m not naïve to that. There’s a sense of grief and, like, “That’s just not how it should be.” We should have children. You know what I mean?

Yes.

In a similar vein, sexual expression is also not a right God has given to us. And this is true even in marriage. I’m very convinced that God has given us our bodies and God has given us a gift of sexual expression, but that does not give us a license to break the boundaries of another person. If my wife were to say to me, “I’m not having sex with you anymore,” I have to deal with that.

Yes, exactly.

I cannot stand on this, like, sexual right. I really can’t. Because her body is still her body. This comes back to the faith commitment I have that the non-physical part of us is reflected in the physical part of us. As people, we have boundaries, and it’s not okay to break them. So I think that’s the first thing, and that’s really hard. Or another thing, like, let’s say something happened to either me or my wife physically and we couldn’t have sex anymore, I still have to be married to her. I’m not released from my vow.

Right, you are not released!

So I think that’s the first thing, and I think that’s a huge hurdle.

I love the heterosexual examples of the unfairness, because that’s the whole thing: “It’s not fair that I can’t express!” So I appreciate the examples from the other way, that is the same unfairness. Even in that unfairness it doesn’t change the standard of God and his expectation.

Right. It is very tempting, even for me as a married man, to start being entitled. But we can’t. If we are to think of ourselves as creatures of God’s creation, made in his image, there’s no place for entitlement. We have to acknowledge that, and we have to abide by that limitation. But I think there’s another issue that’s more difficult. For me, in my life, I have very, very, very seldom had any kind of homosexual urge. It’s just not really a thing for me. So I feel like this issue I’m about to talk about is something that really needs to be talked about by someone who does have same sex attraction. I mean, I’ve basically been attracted to women all my life, and it’s not like I made this choice at some point to be attracted to women, I just am. And there is solace for me, to be honest, knowing that this is actually a good thing. This is a good part of me that actually God wants. God wants us to get married and to have babies and to show communal love in a family, the way God himself exists in a community of love. This is a wonderful thing! But if I were to flip it around and say, “I actually shouldn’t be attracted to women. What God wants me to do is to be attracted to men, not women,” that would be really hard.

Yeah.

I mean, I’d be like, “But…”

“…I just don’t want to.”

Yeah. And in the end, for me as a person who struggles with lust in a heterosexual way, I think it’d be very difficult for someone who was different to hear that kind of message from me. That doesn’t necessarily mean I shouldn’t say that message, but I think it does mean that I should be very, very careful.

And extremely compassionate. Yeah.

And we see this kind of thing in how Paul in the New Testament talks about Christian living. He advises men to hang out with each other and women to hang out with each other and to help each other. He doesn’t say this explicitly, but I think his reason for that is that often across genders, we just don’t understand each other. We think really differently, and it’s hard. There are aspects of my wife’s spiritual life that I can say, “I hear that,” and I mentally assent to it, but I don’t really fully understand her experience. And that makes it hard, particularly in our spiritual life, if she is going through things that I don’t really understand. And I think it’s the path of wisdom for me to be with her, to listen, to pray with her, but to try to speak into that is just not helpful. And it works the other way, too. There are some times in my own spiritual life where I need a man’s perspective.

The other thing that is not lost on me is that there are some other aspects of our identity that exhibit similar dynamics, when you could always say to another person, “Well, you just don’t understand.” We have this same dynamic with black vs white skin, or any kind of difference where there’s some kind of obvious physical distinction between me and another person that I can point to, that’s really clear. It’s really tempting to use that to either take advantage of that difference somehow or to simply ignore the difference and dismiss the other person’s experience. But neither of those are the path of wisdom. Not gender, not race, not even an adult-child difference. God has not given us the gift of our humanity in order for us to take advantage of each other or to ignore the fact that our differences exist.

I like speaking tension, so I am not always trying to resolve tensions. Because I think in our attempt to resolve tensions we quickly want a black and white answer and a lot of it is resolved in community. And I think that’s okay. Yeah, so I can highlight the places of tension and say it’s on us to to read the word faithfully. And to figure out how to resolve those tensions, I think every generation has that responsibility. So I don’t see myself as responsible for making it all okay for everybody.

Yes, I think that’s good and healthy.

This is all good. I think it’s clarity in thinking. I gravitate more to the apologetic side of things, but I thought this would probably need a little bit more biblical frameworks than apologetics.

The other thing that you talked about is wanting to communicate the substance of God’s heart. I think this is something that we can always say. Regardless of who you’re attracted to, I think we can rightly say that the desire in all of us for intimate relationship with another human person, regardless of gender, that desire is actually good and wholesome and comes from God. God wants us to connect with each other, and not just on a superficial level. God wants us to be so close to another person that we would have sex with them. (I hope you understand that I’m using the term God’s “will” in a general sense there.) I think that is comforting.

So I got married when I was 29. Of my group of friends, I was one of the later ones to get married. And there was a time of my life when I really prayed about whether God wanted me to be a monk and have that life. And for about six months I prayed about that. And I kind of came to the end of that, and I was like, “No, being married and having a family is something I really want.” And there were times in my life when, dealing with loneliness and sexual frustration, it was a comfort for me to say to myself, “You know, this thing is actually good, even though this is causing me a lot of frustration right now.” It’s not pleasant to have sexual urges that you cannot fulfill, but I think it is comforting to know that the desire at the bottom of that is good. If we are created in the image of God, and if the physical reflects the non-physical, then to have sex is not simply an animal act, but it really is about the desire to connect to another person, and that desire is good and right. If God himself is three persons in one, then being united with another person is living out God’s community. I really do think that that’s tremendously important. And that God wants that kind of relationship with us, too. It’s not just with each other. There is a sense in which God loves each of us enough that if God could have sex with us, he would.

Right, yes! And when you speak about physical things that sometimes point to spiritual things, or the other way around. For me, when I think of the the whole concept of “knowing” that is all throughout the Old Testament and that sometimes God uses that term for his deep intimacy with us. So for me, I see that parallel of covenant and relationship with the Lord as well. Okay, and then lastly Proverbs.

Right. Proverbs is an interesting book because there’s a very strong sexual subtext in Proverbs but it’s almost all from a man’s perspective. The first nine chapters of Proverbs is where sexuality is explored the most. It’s a series of conversations from a father to a son about who to marry. And basically what this dad says is: When it comes right down to it, don’t go for the woman who wants to sleep with you, especially if she’s married already. Don’t do it! Instead, look for the woman who worships Yahweh has a good head on her shoulders. That’s what you want. Which is really interesting! There’s all kinds of things that can be explored in that. So if I were teaching on sexual identity centered around Proverbs, that’s probably where I would start. With this notion that the advice a father gives to a son is don’t go for the woman who wants to sleep with you, but go for the woman who worships Yahweh and who thinks well and has good sense. Oh, and I should say, the message from the father to the son is he also needs to worship Yahweh. That’s a given. But I think that kind of tension really does highlight what is healthy versus unhealthy masculinity and healthy versus unhealthy femininity.

In the end, what God wants for me as a man is to find my masculinity in him, not in a woman. And that’s the temptation, right? That’s the lure of the woman who wants to sleep with me. Aside from the physical pleasure and that it feels good, spiritually the lure is that I’m looking for validation of my manhood in that person or in that experience as opposed to finding the validation of my manhood in the fact that God has created me to be a man. Does that make sense? And I think that there are lots of things that you can explore in that. I’ve never been a woman, of course, so I can’t speak from a woman’s perspective. But I should think that it would only make sense that it would work a similar way for what drives a woman to be seductive or try to seduce a man. I would imagine it’s a similar thing of trying to find validation of one’s own femininity in this other person or this experience as opposed to the fact that God has created her to be a woman.

I love that. For me, I think that is the link I was looking for. I was feeling like it was three different threads.

Yeah. Oh, another thing. I’ve heard women talk about reading Proverbs 31 and feeling very…

Exhausted.

…like “I can never live up to this,” you know? But I don’t think that’s how an ancient woman would have read it. I think an ancient woman would have read that chapter and said to herself, “Oh, I’m not just a bedroom performer, or a kitchen performer. God wants me to be just as much a productive member of society as a man!” Right? That’s the picture of the woman in Proverbs 31. She is equally as involved in the social community as the man is.

I love it.

And I think that’s the heart of God. I don’t subscribe to this notion that Proverbs 31 is about Lady Wisdom. I don’t think it’s painting a picture of wisdom, I just don’t agree with that. I think the book of Proverbs opens with this advice from a father to a son about the kind of woman he should look for to marry. Then I think Proverbs 31 is kind of like the answer: You don’t want to marry the type of woman who is out to sleep with you but who is out to make their community a better place. And I think that’s a really encouraging and wholesome message.

It is. Yeah, it is. I think also what’s nice is that the text has all the information. Thank you so much. I really appreciate it. I think it would have taken me much longer to try and bring it all together.

Yeah, sometimes it helps just to talk things out! Before we say goodbye, can I pray for you and for your sermon?

That sounds great. Thank you. Thank you so much.