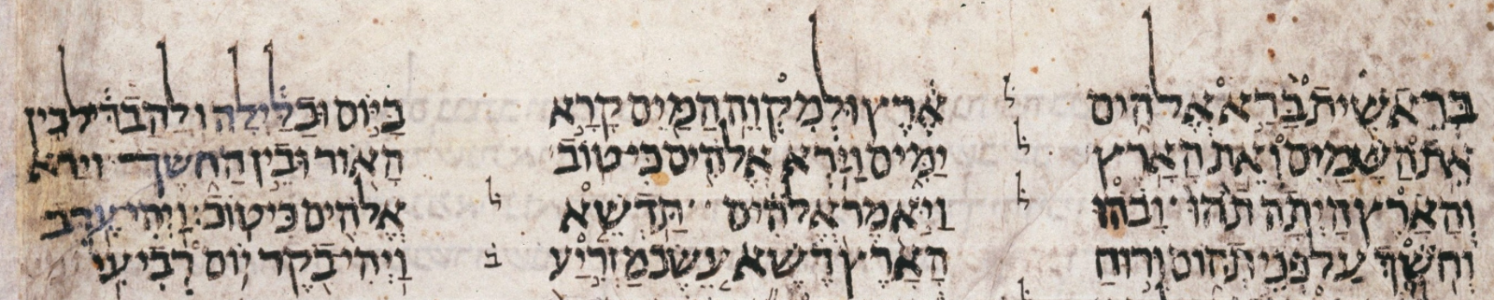

Scripture readings:

Genesis 32:9-13a, 22-32; 33:18-20

Malachi 1:1-5

Matt. 22:34-40

The Lord be with you.

And also with you.

Let us pray.

“O God, you have taught us to keep all your commandments by loving you and loving our neighbor: Grant us the grace of your Holy Spirit, that we may be devoted to you with our whole heart, and united to one another with pure affection; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.”

Book of Common Prayer, p.230

Jacob I have loved, but Esau I have hated.

The words jolt us out of ambivalent observation of Jacob’s story and demand that we choose a side. After all, God Himself chose a side. God says that He loved Jacob and hated Esau. If you were to read the entire story of Genesis from beginning to end, you might understand why God hated Esau, because Esau does not come out looking like a very worthy character in Genesis. But why does God choose Jacob? What’s so lovable about him? After all, it was Jacob, not Esau, who took advantage of his brother to gain the family birthright. It was Jacob who deceived his father and stole Esau’s blessing. It was Jacob who left his home and family and didn’t come back for twenty years. So why does God love this man Jacob – Jacob the “heel-grasper”, Jacob the supplanter, Jacob the liar, Jacob the cheat?

Madeleine L’Engle suggests an answer in her book about Jacob, entitled A Stone for A Pillow. She writes: “All through the great stories, heavenly love is lavished on visibly imperfect people. Scripture asks us to look at Jacob as he really is, to look at ourselves as we really are, and then realize that this is who God loves. God did not love Jacob because he was a cheat, but because he was Jacob. … If God can love Jacob – or any single one of us – as we really are, then it is possible for us to turn in love to those who hurt or confuse us. … And that makes me take a new look at love.” [Madeleine L’Engle, A Stone for a Pillow, The Genesis Trilogy (WaterBrook Press, Colorado Springs, 1997), p.222] That’s exactly what this strange story from Genesis, the most unusual wrestling match in the history of mankind, teaches us – a new look at love, a new look at Jacob, and a new look at God.

Jacob was the younger of twin brothers born to Isaac and Rebekah in southern Palestine. This family had problems from the very beginning. Jacob and Esau fought even while they were in the womb! Isaac favored Esau; Rebekah favored Jacob. Evidently, Esau thought quite highly of his family birthright; so highly, in fact, that he traded it to Jacob for a bowl of stew. But this wasn’t enough for Jacob, who went on to deceive his father Isaac and steal the family blessing, with help from his scheming mother, of course. This was the last straw for Esau, who plots to kill Jacob as soon as his father dies. So what does Jacob do? Probably the same thing you or I would do. He runs for his life. Let’s pick up Jacob’s story in Genesis 28, verse 10:

Now Jacob went out from Beersheba and went toward Haran. So he came to a certain place and stayed there all night because the sun had set.

So Jacob is on the run, at this point he’s probably been on the road for a day or two, maybe three, and he has reached the vicinity of a little town called Luz. Jacob has left everything behind. He is entirely alone. The sun has set on Jacob, and night has come.

And he took one of the stones of that place and put it at his head, and he lay down in that place to sleep. Then he dreamed, and behold, a ladder was set up on the earth, and its top reached to heaven; and there the angels of God were ascending and descending on it. And behold, YHWH stood above it, and said: “I am YHWH, God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac; the land on which you lie I will give to you and your descendants. Also your descendants shall be as the dust of the earth; you shall spread abroad to the west and the east, to the north and the south; and in you and in your seed all the families of the earth shall be blessed. Behold, I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land; for I will not leave you until I have done what I have spoken to you.”

God repeats to Jacob the covenant that he made with both Abraham and Isaac. But there are three additional promises that God makes to Jacob specifically. First, God says that he is with Jacob and promises to keep him wherever he goes. Two, God promises to bring him back to this land, the land of Canaan that lies between the Jordan River and the Great Sea. And three, God will not leave Jacob until He has done everything that He has spoken. That middle promise is important. God promises to bring Jacob back to the land. The Jordan River is an important landmark in this story, because the Jordan River marks the boundary of the land of Canaan. He will have to cross the Jordan River in order to get to his Uncle Laban’s place in Syria, and God promises the bring him back across the Jordan River and back into his homeland. Remember this, because this will become a very important detail later in the story.

Also, notice that these promises of God are unconditional. God doesn’t say that Jacob needs to do anything in order for God to keep his word. It’s an unconditional statement: “I will bring you back to this land.” What does Jacob do in light of this reassuring promise? Probably the same thing you or I would do. He immediately starts bargaining with God for more.

Then Jacob awoke from his sleep and said, “Surely YHWH is in this place, and I did not know it.” And he was afraid and said, “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven!” Then Jacob rose early in the morning, and took the stone that he had put at his head, set it up as a pillar, and poured oil on top of it. And he called the name of that place Bethel; but the name of the place had been Luz previously.

[Let me interject here to say that these practices of setting up rocks, pouring oil over them, then giving that place a special name were all common religious practices in ancient Palestine. In modern terms, we would say that this was an important event in Jacob’s “spiritual journey.” YHWH God has appeared to him, and he commemorates the event appropriately.]

Then Jacob made a vow, saying, “If God will be with me, and keep me in the way that I am going, and give me bread to eat and clothing to put on, so that I come back to my father’s house in peace, then YHWH will be my God. And this stone that I have set as a pillar shall be God’s house, and of all that You give me I will surely give a tenth to You.”

I feel like the text is being generous to Jacob here. The story says that Jacob made a vow to God; it sounds to me like Jacob cut a deal! Essentially, Jacob says to God, “OK, YHWH, you can be my God, but you have to do four things for me first.” The four demands Jacob makes of God are: 1) that God will be with him; 2) that God will keep him in his way, whatever that means; 3) that God will give him bread to eat and clothes to wear; and finally, 4) that God will bring him not just back to his homeland, but to his father’s house.

At this point in the story, I don’t think that Jacob is “sold out” to worshipping YHWH. In fact, if you keep reading, you will find that nowhere does Jacob refer to YHWH as his God; instead, he always refers to YHWH as the God of his father Abraham and of his father Isaac. This little episode between Jacob and God leaves us with some tantalizing questions. Will God keep his promises to Jacob? Will God kowtow to Jacob’s demands? And if not, what will Jacob do? And from an ancient Palestinian perspective, perhaps the most important question of all – if Jacob reneges, what will God do to Jacob? There is relational tension here between God and Jacob, significant tension that we ought not ignore if we are to feel the full impact of this story.

And so the time of Jacob’s night begins. The tables are about to turn, and Jacob the deceiver is going to be deceived. For the next twenty years, things go from bad to worse for Jacob. After seven years of labor, Laban tricks Jacob into marrying the daughter that Jacob doesn’t love and coerces him to work seven additional years to marry the daughter he does love. After those fourteen years are completed, Jacob goes to Laban and asks for his release so that he can get on with his life. Laban insists that Jacob stay, and Jacob agrees on the condition that he be paid with all the brown sheep, and all the specked and spotted goats. Fair enough, Laban says. But notice what Laban does next, picking up the reading in chapter 30, verse 35.

So [Laban] removed that day the male goats that were speckled and spotted, every one that had some white in it, and all the brown ones among the lambs, and gave them into the hand of his sons. Then he put three days’ journey between himself and Jacob, and Jacob fed the rest of Laban’s flocks.

Do you catch what’s going on here? Immediately after making the agreement, Laban takes everything that he said he would pay Jacob and disappears into the wilderness with it, leaving Jacob with all the livestock that, per their agreement, belongs to Laban. Jacob the cheat has been cheated. You can read the whole story for yourself, but at this point God now begins to intervene on behalf of Jacob. No matter how much Laban tries to get the best of Jacob, God works it out so that Jacob always gets the better livestock. Then God speaks to Jacob again:

Then the Angel of God spoke to [Jacob] in a dream, saying: “Jacob.” And [Jacob] said, “Here I am.” And He said, “Lift your eyes now and see, all the rams which leap on the flocks are streaked, speckled, and gray-spotted; for I have seen all that Laban is doing to you. I am the God of Bethel, where you anointed the pillar and where you made a vow to Me. Now arise, get out of this land, and return to the land of your family.”

Twenty long years have passed. Remember the promise of God to Jacob way back in chapter 28, to bring him back to the land? The moment of truth has finally come. Jacob is about to cross the Jordan River and come back to his native homeland. He has sent messengers ahead to Esau his brother, and the messengers have returned saying that Esau is coming to meet him with 400 men. The text doesn’t tell us why Esau brings so many men with him, but Jacob fears the worst – that Esau is out for revenge. So what does Jacob do? Probably the same thing you or I would do. He calls out to God for help.

Then Jacob said, “O God of my father Abraham and God of my father Isaac, the LORD who said to me, ‘Return to your country and to your family, and I will deal well with you’: I am not worthy of the least of all the mercies and of all the truth which You have shown Your servant; for I crossed over this Jordan with [only] my staff, and now I have become two companies…”

Do you hear the difference in Jacob’s tone?

Deliver me, I pray, from the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esau; for I fear him, lest he come and attack me and the mother with the children. For You said, ‘I will surely treat you well, and make your descendants as the sand of the sea, which cannot be numbered for multitude.’ … And he arose that night and took his two wives, his two female servants, and his eleven sons, and crossed over the ford of Jabbok. He took them, sent them over the brook, and sent over what he had. Then Jacob was left alone…

Put yourself in Jacob’s shoes now. You have been banished from your family, exiled from your homeland, taken refuge with your distant uncle who tricked you into marrying both his daughters and cheated you ten times in regard to your payment for shepherding his flocks. And just when God seems to be on the verge of keeping his promise to you to bring you back to your native land, it looks like you are about to lose everything, perhaps even your very life. Oh yes, the lives of your family, too. You have called out to God for help and done everything you can do to protect the ones you love so dearly. It is dark, you are alone, and all indications show that the morning will bring swift disaster.

Does this sound familiar? Have you been in this place, in the desert, in the dark, alone, with no hope? Of course you have. We all have. Take yourself back to that place for a few moments and remember it; then you will be ready to hear the story, to really hear it. I challenge you to resist the urge to mentally jump ahead because you’ve heard the story before and know what happens. Take the story one sentence at a time, just as it unfolds in the text.

Then Jacob was left alone, and a Man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day.

Picture Jacob now, getting ready to camp out for the night. He’s probably not far off the main road. Maybe he’s built a small fire. He’s trying to find as comfortable a place to sleep as he can. Suddenly, a man emerges from the sagebrush and attacks Jacob, which would not have been an uncommon occurrence at this time of history. Jacob doesn’t know who this man is. Jacob defends himself, of course, and they end up wrestling all night long, until the morning light starts to appear in the eastern sky.

Now when He saw that He did not prevail against him, He touched the socket of his hip, and the socket of his hip was out of joint as he wrestled with Him.

Jacob has been wrestling with an unknown stranger and doing very well; when suddenly, with one slight touch of the hand and a monstrous whelp of pain, Jacob is completely disarmed. And in one horrifying moment, he realizes that the person with whom he has been tangling all night long is YHWH Himself, although it doesn’t seem like the full force of this has hit him yet. God speaks:

“Let Me go, for the day breaks.”

Remember how the sun set on Jacob so long ago at Bethel when he slept on a rock and God appeared to him in the dream? Now the sun is about to rise. I imagine Jacob probably utters this next line through angrily clenched teeth, out of breath and between screams of pain.

But he said, “I will not let you go unless You bless me!

Can you hear the cry of the desperate man – the man who would stoop to deceiving his father and stealing from his brother in order to secure a divine blessing?

So He said to him, “What is your name?” He said, “Jacob.” And He said, “Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel; for you have struggled with God and with men, and have prevailed.”

I still remember the first time I translated this verse in my Hebrew class in seminary. I had heard many sermons on this passage before, but none of them really seemed to make much sense. Isn’t struggling against God a bad thing? So why does God praise Jacob for it? And how can God say that Jacob prevailed when clearly, Jacob did NOT prevail? After all, God doesn’t have the dislocated hip right now, Jacob does. But as I came to this verse in my arduous translation work – with books and papers all strewn about my cluttered desk – everything suddenly came together, and the power of the entire story hit me with the unexpected force of one tiny preposition.

I will discuss that in a second, but first let us look at the name given to Jacob, for it is central to the text. Jacob’s old name, Yacov, literally means “heel-grasper.” The name is a double-entendre, not just indicating the circumstances of his birth, clinging to the heel of his twin brother, but also referring to his character as a supplanter, a conniver, a schemer. Now, God gives him a new name, Israel, which is a compound word consisting of the verb SARAH which means “to struggle” and the noun EL, which simply means, “God.” This name Israel can mean either one of two things, depending on whether God is the subject or object of the verb. The name either means “God struggles” or “He struggles with God.” Given the context of the story paired with the explanation God gives for the name, I conclude that this second meaning is the correct one. God no longer identifies Jacob as a scheming conniver but as one who struggles with God. But what does this mean, to struggle “with” God? This little word – the preposition “with” – makes all the difference in the story.

When we read the story in English, we naturally think that Jacob is being praised for struggling against God. But when you read the story in Hebrew, this preposition “with” jumps off the page like a big, bright, flashing neon sign saying, “PAY ATTENTION!” The term used here is the short Hebrew word IM. The simplest definition of the word is, “together with.” Do you see the difference? Jacob is not being praised for struggling against God, but for struggling together with God. The primary definition of this word IM connotes fellowship and companionship. In Hebrew Bible, this is the term of divine presence. It’s the term used in Gen 28 when God promises to be WITH Jacob. It’s the term used in Psalm 23 when David says that, even when he walks through the darkest valley, he will fear no evil because God is WITH him. And it is the term used in that great title for Jesus found in Isaiah 7, IM-MANUEL, God WITH us. God praises Jacob not for struggling against God, but for struggling “together with” God, in fellowship with God; and ironically enough, in fellowship with men.

Now wait just a second. Hold the phone! Jacob has struggled in fellowship with men? Where do you get that from, God? This is Jacob we’re talking about, remember? Jacob, the “heel-grasper” – the supplanter – the liar – the cheat? Where does God get off praising Jacob for struggling “in fellowship with” men? Well, the story is about to tell us, and we’ll see it in just a minute.

This leaves one last phrase to consider. God says, “You have struggled with God and with men, and have prevailed.” How has Jacob prevailed? Jacob has most certainly struggled in his fellowship with Laban. All along the line Jacob could have run away from Laban, but he didn’t. He stayed and continued in fellowship, even though he got taken advantage of again and again and again. When all was said and done, Jacob still ended up with the best livestock. God was not blind to the injustice Jacob suffered at the hands of Laban. And now, God pronounces blessing on Jacob and gives him in a new name in accordance with the character that Jacob has demonstrated. At one time, Jacob was the cheater. Now, Jacob has been cheated, yet Jacob remained in fellowship with Laban until – wait for it – God told him to leave. Do you see the change that has taken place in Jacob’s character? It seems that God saw it, God praises Jacob for it, and God renames Jacob on account of it … Israel, “He struggles in fellowship with God.”

And Jacob said, “Please tell me your name.” And He said, “Why do you ask me my name?” And he blessed him there.

I love God’s question here, mainly because I am wondering the exact same thing. I’m right there with God on this one – “Yes, Jacob, why are you asking God’s name?” This seems like a strange request, especially since God has already told Jacob His name way back in chapter 28. And I wish I had a nice, neat answer to offer, but I don’t. And none of the commentators that I read seem to know, either. So rather than trying to make up something clever, I will let it be, and we can all wonder together. At any rate, the point is that God reaffirms his blessing to Jacob. In the midst of all Jacob’s bargaining, his demanding, his fear and need for reassurance, God has remained consistently true to His word from the very beginning. The only thing lacking is for God to bring Jacob back over the Jordan River, into the land of Canaan, and everything God promised will have come to pass. What hangs in the balance is, “what will Jacob do?” Will he keep his end of the bargain?

So Jacob called the name of the place Peniel; for I have seen God face to face, yet my life is preserved.

Now we have come to the unexpected twist, the iconic irony of this great story. Jacob expects his life to be taken in the morning when he meets Esau, when really, he shouldn’t have even lasted the night. Jacob knows that no one can see the face of God and live, something that we the readers won’t be told until near the end of Exodus. Now, the weight of this divine encounter settles on Jacob’s shoulders, and he is a changed man. God has met him and changed him, not just his name but also his character. But Jacob is wounded now, and he walks with a limp. I bring attention to this small detail to say this: if God has met you in your journey, and now you walk with a limp, don’t be ashamed of it. Instead, do what Jacob did. Jacob’s limp became the memorial of his encounter with God, the means by which his story was told.

Just as he crossed over Penuel the sun rose on him, and he limped on his hip. Therefore to this day the children of Israel do not eat the muscle that shrank, which is on the hip socket, because He touched the socket of Jacob’s hip in the muscle that shrank.

So we’ve seen Jacob’s struggle with God, although we don’t yet know exactly how it’s going to turn out. Let’s turn our attention to Jacob’s struggle with men, particularly with his brother Esau. The text talks about these two relationships in parallel, that is, Jacob’s relationship with God and his relationship with Esau. This story of Jacob wrestling with God comes smack dab in the middle of the story of Jacob’s reconciliation with Esau. And it’s my opinion that when God blesses Jacob for his struggle with men, God is offering his commentary on Jacob’s attempt to reconcile with his brother. So let’s pick up the reading in chapter 33, verse 8.

Then Esau said, “What do you mean by all this company which I met?”

And he said, “These are to find favor in the sight of my lord.”

Now many people interpret this as Jacob trying to buy off Esau in order to assuage his anger, but I don’t think that is the correct interpretation. Let’s keep reading.

But Esau said, “I have enough, my brother; keep what you have for yourself.”

And Jacob said, “No, please, if I have now found favor in your sight, then receive my present from my hand, inasmuch as I have seen your face as though I had seen the face of God, and you were pleased with me.”

And now comes the key phrase:

“Please, take my blessing that is brought to you, because God has dealt graciously with me, and because I have enough.”

So Jacob urged him, and Esau took it.

The key word here is the word blessing. This is the same word that is used back in chapter 27 when Jacob steals the blessing that Isaac intended for Esau. I don’t think that Jacob offers these hordes of gifts to Esau as a bribe, but rather as restitution for what he had taken, the family birthright and the family blessing. At this time in history, the family birthright meant receiving a double share of the father’s inheritance. Twenty years earlier, Jacob had taken advantage of Esau’s weakened condition in an attempt to secure future wealth for himself. Now Jacob is trying to make it right in order to be in fellowship with Esau. Jacob loves his brother, but this love has undergone a journey. Jacob has sinned, and Jacob has repented, and now Jacob makes restitution. The implication of the story is that Esau forgives him, because the text later tells us the Jacob and Esau together bury their father Isaac in the family burial ground.

Jacob’s love for God has gone through a similar journey, but we’re still waiting to see how it’s going to turn out. Well, let’s find out, shall we?

Then Jacob came safely to the city of Shechem, which is in the land of Canaan, when he came from Padan Aram; and he pitched his tent before the city. And he bought the parcel of land, where he had pitched his tent, from the children of Hamor, Shechem’s father, for one hundred pieces of money. Then he erected an altar there and called it El Elohe Israel [which being interpreted means, “God is the God of Israel”].

Ah, there it is. God has now fulfilled all his promises to Jacob from way back at Bethel. He has been with him every step of the way and brought him back across the Jordan to the land of Canaan. But do you see what God has not done? God has not fulfilled all the conditions of Jacob’s vow! Jacob has not come back to his father’s house, he has only come to Shechem. But here, in Shechem, Jacob buys a piece of land and erects an altar to YHWH, similar to what he did twenty years earlier as a desperate young man fleeing for his life. But did you catch the significance of the name that he gives to this altar? He names it, El Elohe Israel, which means, God is the God of Israel. Jacob has repented of his bargaining, his demanding, his “vending machine” theology that demands payment in exchange for services rendered. Instead, he finally bows the knee to YHWH, proclaiming to his idolatrous neighbors through his pile of rocks that YHWH is not only the God of Isaac his father and Abraham his grandfather, but is also his God – Jacob’s God – the God of Israel.

So what would Jacob do? This story tells us that Jacob loved God and loved his brother Esau, just like Jesus commands us now to love God and love our neighbor. But this love came through great struggle. Jacob struggled in his fellowship with God, struggled in his fellowship with men. Now we could debate whether God loved Jacob because of these things or whether Jacob did these things because God loved him first. But all of this misses the point, doesn’t it? The truth of the matter is that Jacob sinned, but he repented and made restitution. Yet the real question for today is not what would Jacob do, but rather, what will you do?

Let us pray.

Almighty God, you have surrounded us with a great cloud of witnesses: Grant that we, encouraged by the good example of your servant Jacob, may persevere in running the race that is set before us, until at least we may with him attain to your eternal joy; through Jesus Christ, the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Book of Common Prayer, p.250

[I preached this sermon at North Baltimore Mennonite Church on Sunday, 1 July 2012.]