Q: I’m trying to get a handle on how long it took to construct the tabernacle. Exo 19:1 says that Israel camped at Sinai in the third month after leaving Egypt. Then Exo 40:17 says that the tabernacle was set up on the first day of the first month of the second year. But after that, Num 10:11 says that the cloud lifted from the tabernacle in the second year, on the twentieth day of the second month. Does this mean that the tabernacle was built in less than a year, and that it only stood in place at Mr Sinai for about a month and a half until the Israelites had to take it down again? How long did it actually take to build the tabernacle, and how long did the Israelites stay at Mt Sinai after coming out of Egypt?

Oh my goodness, these are such great questions! I really love these questions because they point to some dynamics about reading OT literature that are sometimes overlooked but are actually quite important for scholars like myself who believe in divine inspiration and hold to a very high view of Holy Scripture. And sometimes the Bible presents us with details that seem confusing, or, in the extreme, perhaps objectionable or even unbelievable. Such is often the case with timekeeping in the Hebrew Bible. In modern society, we are accustomed to non-relative methods of timekeeping. There is more-or-less a global standard of referring to days, months, and years. We know the exact day, month, and year when we were born, when JFK was shot, when the Declaration of Independence was signed, etc. And we have non-relative means of indicating these dates. 2 May 1978. 22 Nov 1963. 4 July 1776.

But this wasn’t the case in the biblical era. As far as we know, there was no universal standard of timekeeping. Rather, ancient peoples used relative means of keeping time. Events were described as happening in relation to other events that were commonly known at the time of writing. This is the standard method of timekeeping used in all the Bible. The Gospel of Luke states that Jesus was born while the Roman census was taking place that occurred during the reign of Caesar Augustus and when Quirinius was governor of Syria. The book of Daniel says that Nebuchadnezzar first besieged Jerusalem during the third year of the reign of Jehoiakim, king of Judah. Amos the prophet describes his prophetic vision as occurring two years before the earthquake, when Uzziah was king of Judah and Jeroboam II was king of Israel. As modern readers, accustomed to measuring time in non-relative terms, we struggle with the fact that relative methods of measuring time are less precise. It takes a lot more work to piece together a proper timeline. And such is the nature of the questions you’re asking.

[Allow me a brief excursus here to affirm that precision and accuracy are not the same thing. Just because relative methods of timekeeping are less precise than non-relative methods does NOT mean that they are less accurate. Some readers of the Bible encounter convoluted timelines and then rush to the conclusion that certain dates and/or events must not be accurate. But this is not necessarily the case. With non-relative methods of timekeeping, determining accuracy is relatively simple. Any given date is either wrong or right. But with relative methods of timekeeping, determining the accuracy of any given date is much more difficult, because many more temporal markers must be taken into account. So…just because timelines in the Bible seem confusing does not automatically mean that they are incorrect. It just means that we have to work hard to determine if they are correct or incorrect. And in some cases, we may not be able to determine the accuracy of a given date, because we don’t have enough information. Again, this is frustrating for us who are accustomed to more-or-less absolute methods of keeping time, but it’s reality.]

Thankfully, in the case of the Israelites encamping at Mt Sinai and building the tabernacle, we actually have quite a lot of data to work with! And I think we can piece together a reasonably accurate timeline of events from the available evidence. So let’s proceed systematically to examine the evidence that we have. I’ll say here that it helps to be able to read Biblical Hebrew, because as with any language, the Hebrew authors used words and phrases according to prototypical patterns. And it might be semantically important when an author deviates from those prototypical patterns, but we might not be able to see those deviations when the text is translated into English. But we can see those deviations when we read the Hebrew text. And such is the case here, but more on that later.

To untangle the chronological timeline, let’s begin with Exodus 19:1.

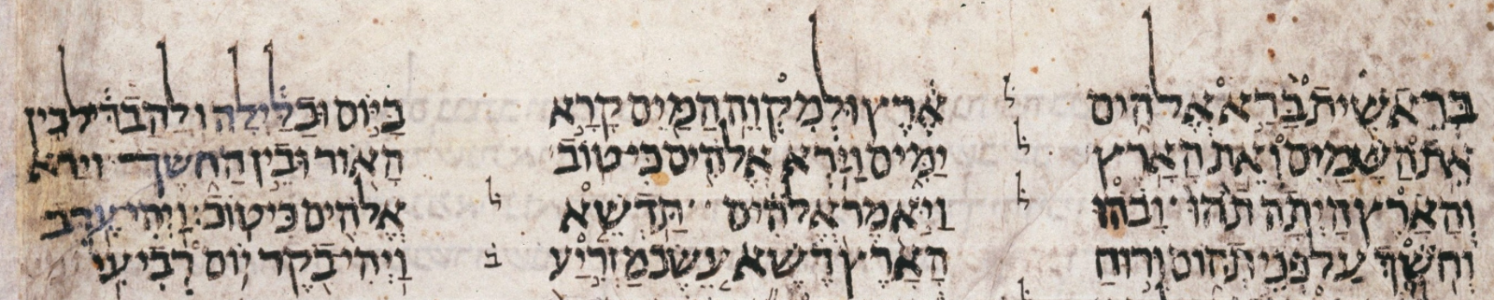

בַּחֹ֙דֶשׁ֙ הַשְּׁלִישִׁ֔י לְצֵ֥את בְּנֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל מֵאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרָ֑יִם בַּיּ֣וֹם הַזֶּ֔ה בָּ֖אוּ מִדְבַּ֥ר סִינָֽי׃

In the third month of the sons of Israel going out from the land of Egypt, on this day, they came to the desert of Sinai.

So the Israelites arrive at Sinai in their third month after having left Egypt. So when they get to Mt Sinai, if they had been carrying a “travel stopwatch,” their stopwatch would be reading two months and change. That little Hebrew phrase “on this day” might suggest that they arrived at Sinai exactly three months (that is, to the day) after leaving Egypt. At least, that’s how the NIV translators appear to understand it. But let’s go back and check. At what point did the “travel stopwatch” start? Rewind to Exodus 12.

The LORD said to Moses and Aaron in Egypt, "This month is to be for you the first month, the first month of your year. Tell the whole community of Israel that on the tenth day of this month each man is to take a lamb for his family, one for each household…Take care of them until the fourteenth day of the month, when all the members of the community of Israel must slaughter them at midnight…This is a day you are to commemorate; for the generations to come you shall celebrate it as a festival to the LORD –– a lasting ordinance…Celebrate the Festival of Unleavened Bread, because it was on this very day that I brought your divisions out of Egypt. Celebrate this day as a lasting ordinance for the generations to come. In the first month you are to eat bread made without yeast, from the evening of the fourteenth day until the evening of the twenty-first day"…At midnight the LORD struck down all the firstborn of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh, who sat on the throne, to the firstborn of the prisoner, who was in the dungeon, and the firstborn of all the livestock as well. Pharaoh and all his officials got up during the night, and there was loud wailing in Egypt, for there was not a house without someone dead. During the night Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron and said, "Up! Leave my people, you and the Israelites! Go, worship the LORD as you have requested. Take your flocks and herds, as you have said, and go"…With the dough the Israelites had brought from Egypt, they baked loaves of unleavened bread. The dough was without yeast because they had been driven out of Egypt and did not have time to prepare food for themselves…Because the LORD kept vigil that night to bring them out of Egypt, on this night all the Israelites are to keep vigil to honor the LORD for the generations to come. [Exodus 12:1-42, NIV]

The narrative in Exodus 12 is actually quite specific here! The text does not say in which specific month of the year the Israelites left Egypt, that is, in which season. But whichever month of the year it was, the Israelites left Egypt on the night of the 14th day of that month. And God is very specific that, from that point on, the Israelites should reckon that month as the first month of their year, and that the Festival of Unleavened Bread will commence on the 14th day of that month. So the “travel stopwatch” began at the end of Day 14 of Month 1 of Year 0. Now, the ancient Israelite calendar was reckoned by the monthly lunar cycles rather than by the annual solar cycle. So let’s begin our chronology accordingly. We’ll set the temporal point of origin as the beginning of the lunar cycle on the month that the Israelites departed Egypt. That’s the beginning of our Year 0. The “travel stopwatch” starts at the end of Day 14 of Month 1 of Year 0. Which means that the Israelites arrive at Sinai sometime during Month 3 of Year 0. That phrase “on that day” in Exodus 19:1 could mean that the Israelites arrived at Sinai on Day 1 of Month 3 of Year 0. Or it could mean that the Israelites arrive at Sinai on Day 15 of Month 3 of Year 0. But it’s sometime during Month 3 of Year 0. That seems clear. And now we can get to the meat of your questions.

The Israelites definitely stay encamped at Mt Sinai for many months, during which time many things happen. God gives the 10 commandments. Moses takes the 40-day “extended stay” tour of Mt Sinai, and he comes back down only to encounter the incident of the golden calf already in progress. Moses apparently takes another 40-day excursion on Mt Sinai, and the Israelites busy themselves with the work of constructing the tabernacle and making all the furnishings that are required for tabernacle worship. The next major time-stamp occurs in Exodus 40.

וַיְדַבֵּ֥ר יְהוָ֖ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֥ה לֵּאמֹֽר׃ בְּיוֹם־הַחֹ֥דֶשׁ הָרִאשׁ֖וֹן בְּאֶחָ֣ד לַחֹ֑דֶשׁ תָּקִ֕ים אֶת־מִשְׁכַּ֖ן אֹ֥הֶל מוֹעֵֽד׃

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: "In the first month, on the first of the month, you shall set up the tabernacle, the tent of meeting." [Exo 40:1-2]

וַיְהִ֞י בַּחֹ֧דֶשׁ הָרִאשׁ֛וֹן בַּשָּׁנָ֥ה הַשֵּׁנִ֖ית בְּאֶחָ֣ד לַחֹ֑דֶשׁ הוּקַ֖ם הַמִּשְׁכָּֽן׃

And it happened in the first month in the second year, in the first of the month, the tabernacle was set up. [Exo 40:17]

We’ve now encountered the first substantive ambiguity in our timeline. If we’re just reading the narrative naturally, it seems like the tabernacle is set up on Day 1 of Month 1 of Year 1. So about nine months after the Israelites arrive at Mt Sinai. If this is correct, then it is certain that the construction of the tabernacle could not have taken longer than 9 months. But we don’t know for certain yet if this is correct, because of that little phrase “in the second year” that appears in Exo 40:17. There are two different ways that we might understand that phrase. It all depends on how the author is reckoning years. The author might have started counting years at the time when the Israelites actually leave Egypt (i.e., with no “year zero”). If so, then the Israelites arrive at Mt Sinai in the third month of the first year, and they set up the tabernacle on the first day of the third month of the second year. That seems the most natural reading. But it’s possible that, when reckoning years, the author is counting the number of times that the calendar turns over (i.e. with a “year zero”). If so, then the phrase “in the second year” would actually mean Day 1 of Month 1 of Year 2 in our reconstructed timeline. This would indicate a much longer period for the construction of the tabernacle, a maximum of 21 months instead of 9 months.

At this point I should note that the Greek Septuagint (i.e., the ancient translation of the Hebrew Bible into Koiné Greek, completed before the time of Jesus) includes a phrase in Exo 40:17 that is not present in the Hebrew Bible. I’ll translate the Greek text and underline the extra phrase:

αὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ μηνὶ τῷ πρώτῳ τῷ δευτέρῳ ἔτει ἐκπορευομένων αὐτῶν ἐξ Αἰγύπτου νουμηνίᾳ ἐστάθη ἡ σκηνή·

And it happened in the first month, the second year of them going out from Egypt, at the new moon, the tabernacle was set up. [Exo 40:17, LXX]

The inclusion of this phrase in the Greek Septuagint does not help our ambiguity, or at least not yet. But it does suggest to us that the author of Exodus 40 is using the same temporal reference point for their “point of origin” as the author of Exodus 19. There appears to be a single method of reckoning years at play, even though we still don’t have enough evidence to conclude whether there is a “year zero” in the mix or not. Fair enough. For now, let’s proceed with what appears to be the most natural reading of the text. In our reconstructed timeline, the tabernacle was set up on Day 1 of Month 1 of Year 1. (And we acknowledge that perhaps the tabernacle was not actually set up until Day 1 of Month 1 of Year 2.)

Of course, when we turn the page after Exodus 40 we encounter the book of Leviticus. And the book of Leviticus contains no time-stamps. Most of the book of Leviticus is comprised of God speaking to Moses and/or Aaron, communicating the laws that should govern the religious and civil life of Israelite society and culture. There are also included a few narrative episodes: the ordination of Aaron and his sons as priests and the initiation of tabernacle worship (Leviticus 8-9), the incident of Nadab and Abihu being struck dead (Leviticus 10), the celebration of the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16 & 23), and the incident of the blasphemer being stoned (Leviticus 24). The very last sentence of Leviticus reads thus:

אֵ֣לֶּה הַמִּצְוֺ֗ת אֲשֶׁ֨ר צִוָּ֧ה יְהוָ֛ה אֶת־מֹשֶׁ֖ה אֶל־בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל בְּהַ֖ר סִינָֽי׃

These are the commands that the LORD commanded Moses for the sons of Israel at the mountain of Sinai. [Lev 27:34]

I attach significance to the fact that this sentence occurs at the very end of the book of Leviticus. I take the author of Leviticus to be indicating that everything written in the book occurred while the Israelite were encamped at Mt Sinai. Now, chronology in the Hebrew Bible can be very tricky. Just because the book of Leviticus comes after the description of the tabernacle being set up does NOT mean necessarily that all the events in the book of Leviticus actually took place after that event. However, the broad narrative of Torah certainly appears to read that way. In other words, a continuous natural reading of Exodus and Leviticus would seem to indicate that everything written in Leviticus took place after the tabernacle was set up and before the Israelites left Mt Sinai. This still doesn’t solve our temporal ambiguity, but it’s more evidence to consider as we turn the page to the book of Numbers. And the early chapters of the book of Numbers contain several time-stamps!

וַיְדַבֵּ֨ר יְהוָ֧ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֛ה בְּמִדְבַּ֥ר סִינַ֖י בְּאֹ֣הֶל מוֹעֵ֑ד בְּאֶחָד֩ לַחֹ֨דֶשׁ הַשֵּׁנִ֜י בַּשָּׁנָ֣ה הַשֵּׁנִ֗ית לְצֵאתָ֛ם מֵאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרַ֖יִם לֵאמֹֽר׃ שְׂא֗וּ אֶת־רֹאשׁ֙ כָּל־עֲדַ֣ת בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל לְמִשְׁפְּחֹתָ֖ם לְבֵ֣ית אֲבֹתָ֑ם בְּמִסְפַּ֣ר שֵׁמ֔וֹת כָּל־זָכָ֖ר לְגֻלְגְּלֹתָֽם׃

And the LORD spoke to Moses in the desert of Sinai in the tent of meeting, in the first day of the second month, in the second year of them going out from the land of Egypt, saying: "Take a census of all of the congregation of the sons of Israel, by their clans, by the house of their fathers, by number of names, every male by their heads." [Num 1:1-2]

So I’ve translated the Hebrew text quite literally here, which produces very awkward phrasing in English. The NIV contains a much more natural reading, and I agree with the meaning provided by the NIV translators. God is commanding Moses to count every single male person in the nation of Israel who has passed the age of 20 years old and to write down their names, listing them according to their tribe and clan affiliation. In other words, this was a very large task. And the text is quite clear about where and when this command was given. The command was given at the desert of Sinai. So the Israelites have not departed from Mt Sinai when this command was given. And this command was given “on the first day of the second month, in the second year of them going out from the land of Egypt.” There are two things to notice immediately here. First, this time-stamp does not yet solve our temporal ambiguity regarding when the tabernacle was set up. It still could be either Day 1 of Month 1 of Year 1 in our reconstructed timeline, or it could be Day 1 of Month 1 of Year 2. However––and this is the second thing we should immediately notice––the author of Numbers here appears to use the same temporal reference point for their “point of origin” as the author of Exodus 19 and Exodus 40. That is, the date of the Israelites departure from Egypt. In other words, it seems that God gave this command to Moses approximately two weeks after the tabernacle was set up. The author of Numbers affirms that Moses and Aaron summoned the nation to begin this task on that same day, the “first day of the second month” (Num 1:18). So far, so good.

The next time-stamp occurs in Numbers 3, and here we get some more temporal information that is very helpful to us. Numbers 3 confirms that the incident of Nadab and Abihu being struck dead occurred in the desert of Sinai (Num 3:4), so before the Israelites left Mt Sinai. Numbers 3:14-15 indicates that God commanded Moses “in the desert of Sinai” to count all the Levites. And not only the Levites, but also the three major clans of the Levite tribe: the clans of Gershon, Kohath, and Merari. This also would have been a large task. And all of this census data is included in the book of Number before the author describes the Israelites leaving Mt Sinai in Num 10:11. Therefore, the natural reading of Torah would seem to indicate that not only did all the events of the book of Leviticus happen at Mt Sinai, but also all the events of Numbers prior to chapter 10. In other words, it seems that all the census data was both collected and recorded while the Israelites were still camped at Mt Sinai. I must admit that the text is not conclusive about this, but it really seems to be the most natural reading of Torah. It also seems that all the events of the book of Leviticus and of Number 1-9 occur after the tabernacle has been set up. In other words, there seems to be a substantial interval of time between when the tabernacle is set up and when the Israelites depart Mt Sinai. File that away for later. But in all of this, we still don’t know if the tabernacle was set up at the beginning of Year 1 or Year 2 of our reconstructed timeline. We’re still gathering data on that point.

The next time-stamp occurs in Numbers 7, which describes everything that was done to dedicate the tabernacle in order to commence daily worship for the Israelites. The text stipulates that this was at least a 12-day process, because each tribe brought their offering of dedication on successive days. Furthermore, the specific Hebrew construction used in Num 7:1 (the preposition בְּ with an infinitive construct) indicates contemporaneous action, which would seem to indicate that the dedication of the tabernacle began immediately after it was set up. So the author of Numbers appears to have gone back in time a month. That is, it seems like the dedication of the tabernacle occurred during Month 1––of either Year 1 or Year 2, we still don’t know for sure––but before God commanded Moses to take the census of Israelite men.

So let’s take stock of our reconstructed timeline thus far:

- Year 0, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites depart Egypt

- Year 0, Month 3, Day ?? –– the Israelites arrive at Sinai

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 1 –– the tabernacle is set up

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 1ff –– the tabernacle is dedicated

- Year 1 or 2, Month 2, Day 1 –– the census of Israelite men commences

- Unknown –– the death of Nadab & Abihu, the Day of Atonement, and the execution of the blasphemer

The next time-stamp occurs in Numbers 9.

וַיְדַבֵּ֣ר יְהוָ֣ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֣ה בְמִדְבַּר־סִ֠ינַי בַּשָּׁנָ֨ה הַשֵּׁנִ֜ית לְצֵאתָ֨ם מֵאֶ֧רֶץ מִצְרַ֛יִם בַּחֹ֥דֶשׁ הָרִאשׁ֖וֹן לֵאמֹֽר׃ וְיַעֲשׂ֧וּ בְנֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֛ל אֶת־הַפָּ֖סַח בְּמוֹעֲדֽוֹ׃ בְּאַרְבָּעָ֣ה עָשָֽׂר־י֠וֹם בַּחֹ֨דֶשׁ הַזֶּ֜ה בֵּ֧ין הָֽעֲרְבַּ֛יִם תַּעֲשׂ֥וּ אֹת֖וֹ בְּמוֹעֲד֑וֹ כְּכָל־חֻקֹּתָ֥יו וּכְכָל־מִשְׁפָּטָ֖יו תַּעֲשׂ֥וּ אֹתֽוֹ׃ וַיְדַבֵּ֥ר מֹשֶׁ֛ה אֶל־בְּנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל לַעֲשֹׂ֥ת הַפָּֽסַח׃ וַיַּעֲשׂ֣וּ אֶת־הַפֶּ֡סַח בָּרִאשׁ֡וֹן בְּאַרְבָּעָה֩ עָשָׂ֨ר י֥וֹם לַחֹ֛דֶשׁ בֵּ֥ין הָעַרְבַּ֖יִם בְּמִדְבַּ֣ר סִינָ֑י כְּ֠כֹל אֲשֶׁ֨ר צִוָּ֤ה יְהוָה֙ אֶת־מֹשֶׁ֔ה כֵּ֥ן עָשׂ֖וּ בְּנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

And the LORD spoke to Moses in the desert of Sinai, in the second year of them going out from the land of Egypt, in the first month, saying: "Now the sons of Israel shall perform the Passover at its appointed time. In the fourteenth day of this month, between the evening times, they shall perform it at its appointed time. According to all of its statutes and all of its commands they shall perform it." So Moses spoke to the sons of Israel to perform the Passover. And they performed the Passover at the first in the fourteenth day of the month, between the evening times, in the desert of Sinai. According to all that the LORD commanded Moses, thus did the sons of Israel perform. [Num 9:1-5]

[NOTE: the phrase “between the evening times” almost certainly refers to the period of time between when the sun sets below the horizon and when daylight is no longer visible in the sky, i.e., “twilight.”]

Here we should take note of the same two things as the time-stamp at the beginning of the book of Numbers. This time-stamp does not clarify the ambiguity of years, but it appears to use the same temporal reference point as before for its “point of origin” for the timeline. The command to celebrate the Passover comes sometime during the two week period following the tabernacle being set up, whether that be in Year 1 or Year 2 of our reconstructed timeline. This also appears to be the first official celebration of Passover as an institutional festival, which would perhaps indicate that the tabernacle was set up in Year 1 rather than Year 2. If it was Year 2, then did the Israelites just not celebrate Passover during Year 1, while the tabernacle was presumably still under construction? I mean, God seemed pretty adamant back in Exodus 12 that the Passover was to be celebrated every year. It doesn’t make much sense that they would just skip it, especially on the very first anniversary of the exodus event! It makes perfect sense that the Israelites would celebrate the first institutional festival of the Passover on the actual first anniversary of the exodus event. So a Year 1 timeline for the construction of the tabernacle is looking better and better, but the conclusion is still not airtight yet. But again, let’s recap the timeline:

- Year 0, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites depart Egypt

- Year 0, Month 3, Day ?? –– the Israelites arrive at Sinai

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 1 –– the tabernacle is set up

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 1ff –– the tabernacle is dedicated

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites celebrate Passover

- Year 1 or 2, Month 2, Day 1 –– the census of Israelite men commences

- Unknown –– the death of Nadab & Abihu, the Day of Atonement, and the execution of the blasphemer

Now we come to the all important time-stamp, the date when the Israelites actually leave Mt Sinai. This is found in Numbers 10:11-12.

וַיְהִ֞י בַּשָּׁנָ֧ה הַשֵּׁנִ֛ית בַּחֹ֥דֶשׁ הַשֵּׁנִ֖י בְּעֶשְׂרִ֣ים בַּחֹ֑דֶשׁ נַעֲלָה֙ הֶֽעָנָ֔ן מֵעַ֖ל מִשְׁכַּ֥ן הָעֵדֻֽת׃ וַיִּסְע֧וּ בְנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֛ל לְמַסְעֵיהֶ֖ם מִמִּדְבַּ֣ר סִינָ֑י וַיִּשְׁכֹּ֥ן הֶעָנָ֖ן בְּמִדְבַּ֥ר פָּארָֽן׃

And it happened in the second year, in the second month, in the twentieth day of the month, that the cloud lifted from over the tabernacle of the congregation. And the sons of Israel set out by their stages from the desert of Sinai. And the cloud dwelt in the desert of Paran. [Num 10:11-12]

Do you see what is different about this time-stamp from all the previous ones? The temporal reference point of origination is omitted! The author does NOT say “the second year of their going out from the land of Egypt.” The author simply says, “in the second year.” Hmmm. Maybe this difference is important, and maybe it’s not, but it’s certainly noteworthy for the observant reader. Let’s see what we might make of this. Since we now have a definite date for when the Israelites leave Mt Sinai, perhaps we can figure out which of our temporal options make sense.

Let’s start with the assumption that the reckoning of years in Number 10:11 is the same as all the previous time stamps, with the same ambiguity. The reconstructed timeline now looks like this:

- Year 0, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites depart Egypt

- Year 0, Month 3, Day ?? –– the Israelites arrive at Sinai

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 1 –– the tabernacle is set up

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 1ff –– the tabernacle is dedicated

- Year 1 or 2, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites celebrate Passover

- Year 1 or 2, Month 2, Day 1 –– the census of Israelite men commences

- Unknown –– the death of Nadab & Abihu, the Day of Atonement, and the stoning of the blasphemer

- Year 1 or 2, Month 2, Day 20 –– the cloud lifts and the Israelite depart Sinai

So let’s examine each of these two options in turn. Let us suppose that the tabernacle was constructed in Year 1 and that the cloud lifted the following month. This would yield the result that the Israelites spent a grand total of 11 months encamped at Mt Sinai. The reconstructed timeline would look like this:

“SHORT” OPTION

- Year 0, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites leave Egypt

- Year 0, Month 3, Day ?? –– the Israelites arrive at Sinai

- Year 1, Month 1, Day 1 –– the tabernacle is set up

- Year 1, Month 1, Day 1ff –– the tabernacle is dedicated

- Year 1, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites celebrate Passover

- Year 1, Month 2, Day 1 –– the census of Israelite men commences

- Unknown –– the death of Nadab & Abihu, the Day of Atonement, and the stoning of the blasphemer

- Year 1, Month 2, Day 20 –– the cloud lifts and the Israelite depart Sinai

Under this timeline, if all the events of Leviticus and Number 1-9 actually occurred while the Israelites were encamped at Mt Sinai, then that would mean that the entire census of Israelite men was completed in three weeks! It also brings up questions about when the three unknown incidents actually occurred. It strains credulity to think that all three of these events happened in the seven weeks between the tabernacle being set up and the cloud lifting! One might say, “Well, the chronology isn’t certain. Maybe those three unknown events actually happened either before the tabernacle was set up and/or after the Israelites left Sinai.” Yes, maybe, but the general narrative of Torah certainly doesn’t seem to read that way. The “short” option really seems unrealistic, given all the other details of the story.

Now at this point is where some readers of the Hebrew Bible might throw up their hands and say, “See? Biblical timelines are inaccurate and therefore must have been fabricated.” And to that I respond: “Not so fast, my friend. Let’s explore all the options.” So by all means, let’s keep exploring the options.

“LONG” OPTION

- Year 0, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites leave Egypt

- Year 0, Month 3, Day ?? –– the Israelites arrive at Sinai

- Unknown –– the death of Nadab & Abihu, the Day of Atonement, and the stoning of the blasphemer

- Year 2, Month 1, Day 1 –– the tabernacle is set up

- Year 2, Month 1, Day 1ff –– the tabernacle is dedicated

- Year 2, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites celebrate Passover

- Year 2, Month 2, Day 1 –– the census of Israelite men commences

- Year 2, Month 2, Day 20 –– the cloud lifts and the Israelite depart Sinai

Well now, this timeline still has some problems, but it looks better than the first one! This option allows for a significant passage of time at Mt Sinai, which seems to accord with the sense of the overall narrative of Torah. But this option still would seem to indicate that the census of Israelite men occurred in less than three weeks. And again, the sense I get from reading Leviticus is that the three unknown events occurred after the tabernacle was set up rather than before it. To me, this timeline still strains credulity too much. But we still have at least one more option to explore…

Perhaps the omission of the temporal reference point of the exodus event in the phraseology of Numbers 10:11 is a textual indicator that the reckoning of years in that instance is different from the reckoning of years used previously. When Num 10:11 says “in the second year,” perhaps the author in that instance is counting the number of times the calendar has turned over, whereas in all the previous instances the author has been counting the progression of years since the temporal point of origin. I know, to say it that way is kind of a mind-bender. Let me express it this way. Perhaps the “second year” in Num 10:11 is different than the “second year of their going out from the land of Egypt” in Exo 40:17, Num 1:1 and Num 9:1. This would yield the following reconstructed timeline:

MULTIPLE TIMELINE OPTION

- Year 0, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites depart Egypt

- Year 0, Month 3, Day ?? –– the Israelites arrive at Sinai

- Year 1, Month 1, Day 1 –– the tabernacle is set up

- Year 1, Month 1, Day 1ff –– the tabernacle is dedicated

- Year 1, Month 1, Day 14 –– the Israelites celebrate Passover

- Year 1, Month 2, Day 1 –– the census of Israelite men commences

- Unknown –– the death of Nadab & Abihu

- Year 1, Month 7, Day 10 –– the Israelites celebrate the Day of Atonement

- Unknown –– the stoning of the blasphemer

- Year 2, Month 2, Day 20 –– the cloud lifts and the Israelites depart Sinai

This proposed timeline appears to harmonize all the time-stamps, and it intuitively makes coherent sense of the general narrative of Torah. Granted, the events are not always told in chronological order, but that is not really a problem in the Bible. We know already that the biblical authors were not bound by chronology when telling their stories but had other ways of organizing narratives. This timeline allows a reasonable amount of time for the construction of the tabernacle, about 8 months. This timeline also allows a full year to complete the multiple censuses commanded by God while encamped at Mt Sinai, as the narrative seems to indicate. Furthermore, this timeline also allows for the celebration of the Day of Atonement at Sinai after the construction of the tabernacle, as the narrative also seems to indicate. There is also plenty of time for the incident of the death of Nadab and Abihu to occur both after the construction of the tabernacle and before the Day of Atonement, as indicated by Leviticus 16:1. There is no definitive time-stamp given for the incident of the stoning of the blasphemer, but the book of Leviticus includes it after the Day of Atonement. This timeline allows for that, too.

This, then, is my conclusion. It took no more than about 8 months to construct the tabernacle, and it was set up on the first day of Israelite new year after departing Egypt. The Israelites remained encamped at Mt Sinai for a full year after that, during which time they were busy counting all the men and doing all the things necessary to carry out all their rituals of daily worship and annual festivals. They didn’t leave Sinai until the second month of the following year, meaning that they were encamped at Mt Sinai for about 23 months, or nearly two full years.

But the larger lesson is this: Just because things in the Bible don’t appear to make sense at first glance doesn’t mean that they are inaccurate or contradictory or false. We may need to work harder and/or think further outside our pre-conceived boxes in order to understand the text we’re reading.