When Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them on the road through the Philistine country, though that was shorter…God led the people around by the desert road toward the Red Sea…By day the LORD went ahead of them in a pillar of cloud to guide them on their way and by night in a pillar of fire to give them light, so that they could travel by day or night. Neither the pillar of cloud by day nor the pillar of fire by night left its place in front of the people.

Then the LORD said to Moses, “Tell the Israelites to turn back and encamp near Pi Hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea. They are to camp by the sea, directly opposite Baal Zephon. Pharaoh will think, ‘The Israelites are wandering around the land in confusion, hemmed in by the desert.'”…So the Israelites did this.

When the king of Egypt was told that the people had fled, Pharaoh and his officials changed their minds about them…So he had his chariot made ready and took his army with him…The LORD hardened the heart of Pharaoh king of Egypt, so that he pursued the Israelites–all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots, horsemen and troops–pursued the Israelites and overtook them as they camped by the sea near Pi Hahiroth, opposite Baal Zephon.

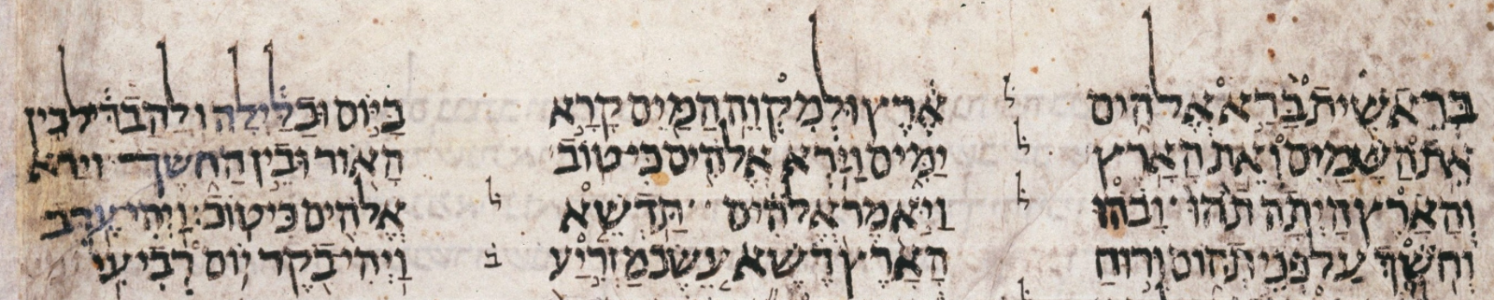

Exodus 13:17-14:9

This story is so compelling to me. In case you don’t immediately know the context, this is the set-up for the Red Sea crossing in the book of Exodus. What’s so compelling to me about this story is how God orchestrates every single detail of it. And it makes absolutely no sense. [Well, unless God intends to do something so incredibly mind-blowing you never would believe it.].

If we were to speak in simple militaristic terms, God leads the Israelites into a trap. Then God Himself springs the trap that, apparently, He Himself has set. Do you see that? The Israelites are on their way out of Egypt, and then God tells them to … wait for it … Turn. Around. Then God tells them to go to a very specific place, “between Migdol and the sea.” We don’t know exactly what this place “Migdol” refers to, but in Hebrew the word means “tower” (presumably a fortified place). This specific place is near Pi Hahiroth and opposite Baal Zephon––again, two places where we don’t know the precise locations. But God wants them to camp by the sea. And apparently, there’s only one way out of this place, which is back the way they came.

At this point, the author says that God hardened the heart of Pharaoh so that he and his army would chase the Israelites. God explicitly says what Pharaoh and his officials will think. The Egyptians observe that the Israelites have gone to a place that they can’t get out of, because they are “hemmed in by the desert.” So the Israelites are encamped by the sea with the desert all around, and then they see the Egyptians blocking the only route of escape.

Every single one of these happenings and events are directly orchestrated by God. The author is very careful to tell us this. The Israelites have been following God, exactly like they’re supposed to do. And they are trapped. Trapped “between Migdol and the sea.” The story continues…

As Pharaoh approached, the Israelites looked up, and there were the Egyptians marching after them. They were terrified and cried out to the LORD.

Exodus 14:10

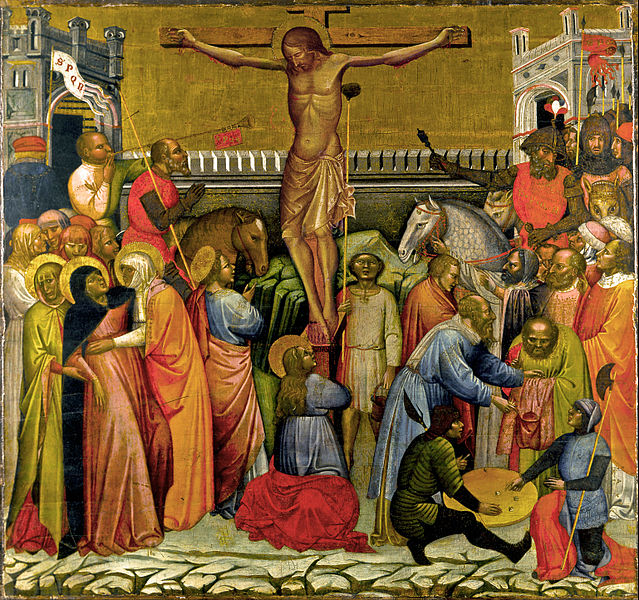

[Of course, you know how the story progresses. The Israelites complain to Moses. Moses cries out to God. God tells Moses to lift up his rod and tells the people to go forward, then God divides the waters and the Israelites cross the sea on dry land. The Egyptian army pursues them into the sea and are swallowed by the abyss when the waters return to their normal state.]

But I’ve stopped the story at this exact point for a reason. The Israelites are terrified, understandably so. The Israelites cry out to God, and so they should. God is the one who got them into this mess in the first place! [Except it’s not a mess. It simply appears that way in the moment. But I’m getting ahead of myself again!] What I want to point out here at this precise moment in the story is how terrifying this mode of travel is. The Israelites are, literally, “following God.” Into the desert. Into the unknown. Into certain death, for they know that they will all die eventually. Pause a moment.

Now fast forward…across the Red Sea to the foot of Mt Sinai, where the Israelites camped for over a year before they continue their journey home…

This is how it continued to be…Whenever the cloud lifted from above the Tent, the Israelites set out; wherever the cloud settled, the Israelites encamped. As long as the cloud stayed over the tabernacle, they remained in camp. When the cloud remained over the tabernacle a long time, the Israelites obeyed the LORD’s order and did not set out. Sometimes the cloud was over the tabernacle only a few days; at the LORD’s command they would encamp, and then at his command they would set out. Sometimes the cloud stayed only from evening till morning, and when it lifted in the morning, they set out. Whether by day or by night, whenever the cloud lifted, they set out. Whether the cloud stayed over the tabernacle for two days or a month or a year, they Israelites would remain in camp and not set out; but when it lifted, they would set out. At the LORD’s command they encamped, and at the LORD’s command they set out.

Numbers 9:16-23

This paragraph clearly communicates that this literal practice of “following God” was the normative mode of travel for the Israelites from the time they left Egypt until the time they entered their ancestral homeland about 40 years later. When God took a step, the Israelites took a step. When God stopped, the Israelites stopped. When God turned right, the Israelites turned right. When God turned left, the Israelites turned left. When God went up over the mountains, the Israelites went up over the mountains. When God famously went through the Rea Sea, the Israelites also went through the Red Sea.

As Christians, we often conceptualize the spiritual life as a journey of inner transformation, and that is wholly appropriate. Most of the New Testament is concerned with this very thing…how the people of God should be inwardly formed more into the likeness of Jesus. Over time, we should grow in love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, self-control, etc. But if we see this journey of the Israelites through the desert as somehow instructive for our spiritual life as Christians, then there is more to it than simply an internal journey. We can see some external evidence of inner change taking place among the Israelites as they travel through the desert. But the journey through the desert is equally external as well as internal, as demonstrated by this mode of travel. We can say in a very literal sense that the Israelites “walked about with God,” which is the phrase the author of Genesis uses to describe both Enoch (Gen 5:22) and Noah (Gen 6:9). God determined the actual path they traveled through the desert.

Now let’s fast forward again…this time all the way through the incarnation, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus to St Paul the apostle writing his letter to the Romans…

Therefore, there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus, because through Christ Jesus the law of the Spirit of life set me free from the law of sin and death…[God’s Son] condemned sin in sinful man, in order that the righteous requirements of the law might be fully met in us, who do not live according to the sinful nature but according to the Spirit…Those who live in accordance with the Spirit have their minds set on what the Spirit desires. The mind of sinful man is death, but the mind controlled by the Spirit of life is life and peace…You, however, are controlled not by the sinful nature but by the Spirit, if the Spirit of God lives in you…Therefore, we have an obligation––but it is not to the sinful nature, to live according to it. For if you live according to the sinful nature, you will die; but if by the Spirit you put to death the misdeeds of the body, you will live, because those who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God.

Romans 8:1-14 (emphasis added)

The Israelites were led by the Spirit of God. They thought they were going to die. But they lived.

The Christian spiritual life means to keep in step with God’s Holy Spirit. When He steps, we step. When He turns right, we turn right. When He turns left, we turn left. When He stops, we stop. St Paul is primarily talking about internal transformation here, but he uses a metaphor grounded in the Israelite story of the Old Testament. To walk in accordance with the Holy Spirit means to be led by Him, even controlled by Him. It’s not only internal transformation; it’s external direction as well.

Here’s the moral of the story. If you ever find yourself “between Migdol and the sea,” and you feel terrified because the Egyptians are bearing down upon you, cry out to God. Perhaps, like the Israelites, He Himself led you there. It’s not a mistake. Trust God.

Or, perhaps more likely, you fear to “walk about with God” because God might lead you into that very place––”between Migdol and the sea.” If that is you, cry out to God. Take courage. Follow God, and you will live.