Q: My understanding of the Catholic theology of sex is that the only sex that is without sin is intercourse between a husband and wife that is “open to life” –– meaning that the only permissible means of birth control is having sexual intercourse only during a wife’s infertile periods. What bothers me most about this teaching is that it may be true. If so, this means that the use of condoms and/or a vasectomy as a means of birth control would be willful disobedience to the will of God. I have a hard time determining whether or not this theological teaching is an articulation of God’s truth or a form of man’s legalism. What does the Bible say?

Before launching into this issue, I want to thank this reader for asking such an honest and vulnerable question, and for giving me permission to post it here. It is an honor to be asked this kind of ethical question of another person, something that I do not take for granted. I want to honor the reader in return by offering the best answer I can. Since this blog is dedicated to reading the OT and not to the particulars of Catholic theology, in this post I will not seek to argue either for or against the teaching of the Catholic church regarding sexual ethics. But the reader here is quite correct that neither condoms nor a vasectomy are acceptable means of birth control as sexual ethics are defined in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (see ¶2370, p.629).

[Note: I myself am Anglican, not Catholic, although generally I have a high regard for the ethical teachings of the Catholic church.]

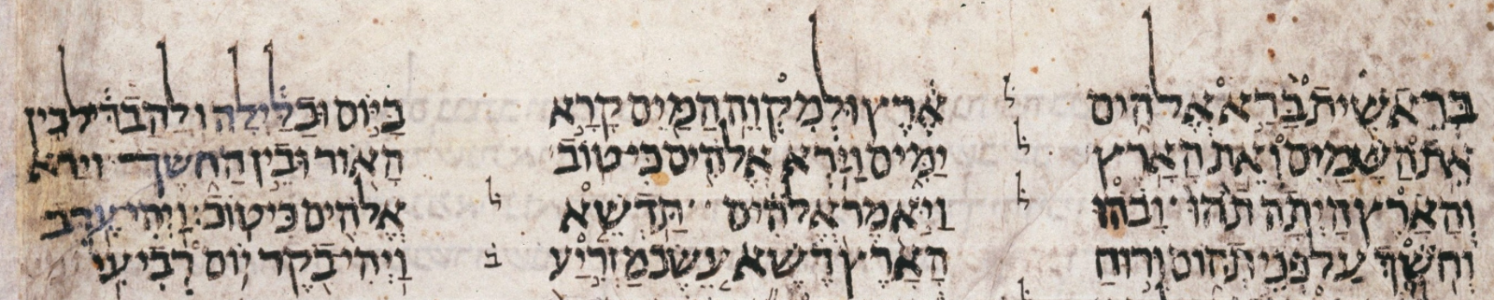

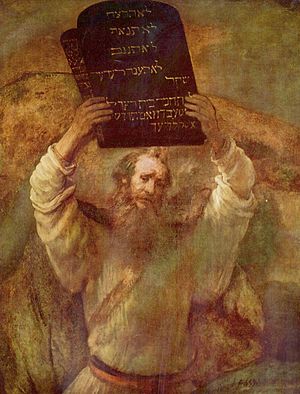

Rather, my aim in this post is to investigate the perspective of the OT text in regard to sexual ethics, particularly in the creation narratives (i.e. Genesis 1-4). In short, I’m seeking to answer the question, What is a creation theology of sex? I will then apply the results of that theological investigation in order to provide some kind of answer to the question at hand. But I need to offer a caveat that, in my opinion, there are many aspects of life and spirituality concerning which the Bible does not prescribe rigid laws. God has created us as creatures of conscience, which is a gift of God to us to help us navigate life. In my opinion, the issue of whether the specific Catholic teaching being referenced here is “an articulation of God’s truth or a form of man’s legalism” finally can only be answered by the married couple themselves in their relationship with God.

A creation theology of sex must start with Gen 1:26-28.

Then God said, “Let Us make humanity in Our image, after Our resemblance; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the flying creatures of the heavens, and over the beasts and over all the earth, and over all the crawling creatures that crawl on the earth.”

So God created the human race in His image;

in the image of God He created it;

male and female He created them.

And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the flying creatures of the heavens, and over all the living creatures that crawl on the earth.”

In sum, there are three theological arguments to be made from this short paragraph of text concerning the human condition in regard to sexuality. First, all humanity is created in the image of God, both male and female persons. In other words, both masculinity and femininity together express the image and likeness of God. Neither masculinity alone nor femininity alone can suffice, and neither gender identity is more or less “divine” than the other. Rather, it is the case that masculinity requires femininity, and femininity requires masculinity, both simultaneously, in order to fully express the image of God. Second, the entire human race, both male and female, is blessed by God. There is a sanctity to being human that extends beyond simply the fact of having been created. As humans, we stand in a special relationship to God; even as sinners, we are not cursed. The ground has been cursed, but we as people remain blessed simply on the basis of being human. Thirdly, all humanity has an inherent obligation to our Creator to procreate for the purpose of filling and managing the planet Earth. This is a collective responsibility to God that we bear as a human race, hence the human phenomenon of sexuality (in all its enormous complexity).

For each of us as human beings, our maleness or femaleness––although marred by sin–– is God’s creative design for our personhood. We are engendered sexual beings because we are human beings, and to be an engendered sexual being is profoundly good and right and wholesome, in and of itself, with no qualifications, because we are blessed by God. In other words, a person’s sexual identity intrinsically carries no shame whatsoever. Period. Full stop. But we mustn’t end there, because the third axiom adds a dimension of purpose to our sexual identity as engendered persons. Collectively as humans, God has created us as sexual beings to carry out a specific function in the world, that is, to procreate and manage the planet that God has entrusted to us to steward. And if sexual identity is created for a specific function, then it is only natural that there could be limitations placed on sexual expression in order to ensure that its function is fulfilled. For example, let’s say I make a hammer for the purpose of driving a nail, but try to drive a screw instead. I could cause unnecessary damage because I have acted outside the inherent limitations of the thing that I have made. These limitations derive from the intended purpose for which I, the maker, designed the hammer.

But there is still more to say about this notion of God’s expressed purpose/function for human sexuality. This brings us to Genesis 2:24.

Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother, and clings to his wife; and they become one flesh.

Here the narrative is terse and does not explain what is meant by the term “one flesh,” but it is clear from Paul’s writings in the New Testament that he understands the term as a reference to sexual union (see 1 Cor 6:12-20). So in addition to the procreating function of sexual expression that is explicit commanded in Genesis 1, there is also a uniting function for sexual expression that is implicitly stated in Genesis 2. God has created sexuality as the means by which a man and woman both unite to each other and procreate with one another. So far, so good, says the Catholic catechism.

But Catholic doctrine then takes this a step further, affirming that God has created these two functions for human sexuality as both universal and inseparable; and this makes all the difference for the question being asked. Part Three of the Catholic catechism, entitled “Life in Christ,” includes a section on the “fecundity of marriage”:

¶2366. Fecundity is a gift, an end of marriage, for conjugal love naturally tends to be fruitful. A child does not come from outside as something added on to the mutual love of the spouses, but springs from the very heart of that mutual giving, as its fruit and fulfillment. So the Church, which is “on the side of life” teaches that “it is necessary that each and every marriage act remain ordered per se to the procreation of human life.” “This particular doctrine, expounded on numerous occasions by the Magisterium, is based on the inseparable connection, established by God, which man on his own initiative may not break, between the unitive significance and the procreative significance which are both inherent to the marriage act” [Catechism of the Catholic Church, p.628].

The definitive element here is the phrase “each and every marriage act”––meaning sexual intercourse––which is NOT a quote from Holy Scripture but rather from the Catholic doctrinal document called Humanae vitae (Eng. “human life”). Thus, the primary question being asked by the reader is whether the Catholic catechism is correct when it affirms that God has indeed created these two functions of sexuality as both existentially inseparable and universally applicable. If so, then the Catholic doctrine is unassailable and must be followed in order to adhere to God’s natural law for human sexuality. But if not, then there is room for varied application of these two functional principles. So how can one evaluate whether the Catholic claims are indeed correct?

First, one should note that the Bible itself does not stipulate either the inseparability or universality of these two functions for human sexuality. This decision is left to the reader, which may itself imply a kind of answer to the question; that is, perhaps this question is rightly considered a matter of personal conscience (similar to Paul’s advice in Romans 14 concerning the Christian observance of the Sabbath), which would of itself negate the absolute “universal applicability” of these functions.

Secondly, the fact that the Catholic catechism specifically affirms that children are a “gift” from God also implies that perhaps the unitive and procreative functions of human sexuality are not quite as inseparable as the catechism states. This seems reflected in the Genesis narrative itself, since the procreative function of sexuality is stated as an explicit command (Gen 1:28) whereas the the unitive function is stated as an implicit fact (Gen 2:24). This would seem to indicate that the unitive function is a genuine constitutive reality of human sexuality––that is, that sexual expression serves to unite persons whether we like it or not. But this is plainly untrue concerning the procreative function of human sexuality, because not all sex leads to procreation, as many people can painfully attest.

Thirdly, there are several instances in the Scriptures where the biblical writers as well as Jesus Himself affirm and emphasize the unitive function of sexuality as well as God’s desire that such a union should not be broken (see Gen 20:1-18; Prov 5:15-23; Mal 2:10-16; Matt 5:27-32, 19:1-12; Mark 10:1-12; 1 Cor 7:1-16). However, I do not find the same kind of emphasis in Scripture concerning the procreative function. The biblical writers seem quite concerned that married people should be faithful to one another and remain united to one another. The biblical writers do not seem concerned nearly so much that married people should be producing children. I think the biblical exegete can make a compelling case that God has created an imbalance in this functions for human sexuality, with greater importance on the unitive function but not to the negation of the procreative function.

In the end, I cannot specifically answer the question of the reader, whether the Catholic sexual ethic is divine truth or human legalism. However, I think I can confidently say that the Catholic sexual ethic exceeds a biblical creation theology, i.e. it goes beyond what is expressed in the creation narratives. But whether the Catholic ethic exceeds the bounds of natural theology (a.k.a. natural law) is quite another matter, one to which I must appeal to conscience.